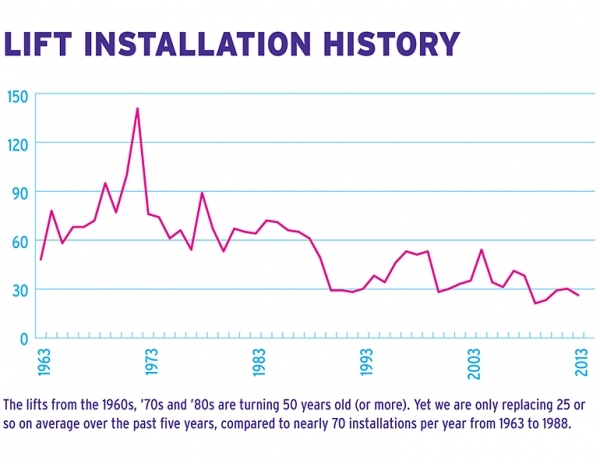

The question arises due to the exponentially increasing number of old lifts operating. The lifts from the “lift boom” of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s are turning 50 years old (or more), hitting a critical age. Yet we are only replacing half as many lifts per year, 25 or so average over the past five years, compared to the 54 per year average for the past 50 years—and the average of nearly 70 per year for the 25 years from 1963 to 1988. (See chart.) This inverse relationship means the average age of the lifts being operated in the U.S. is increasing, with a growing number approaching the end of their useful life.

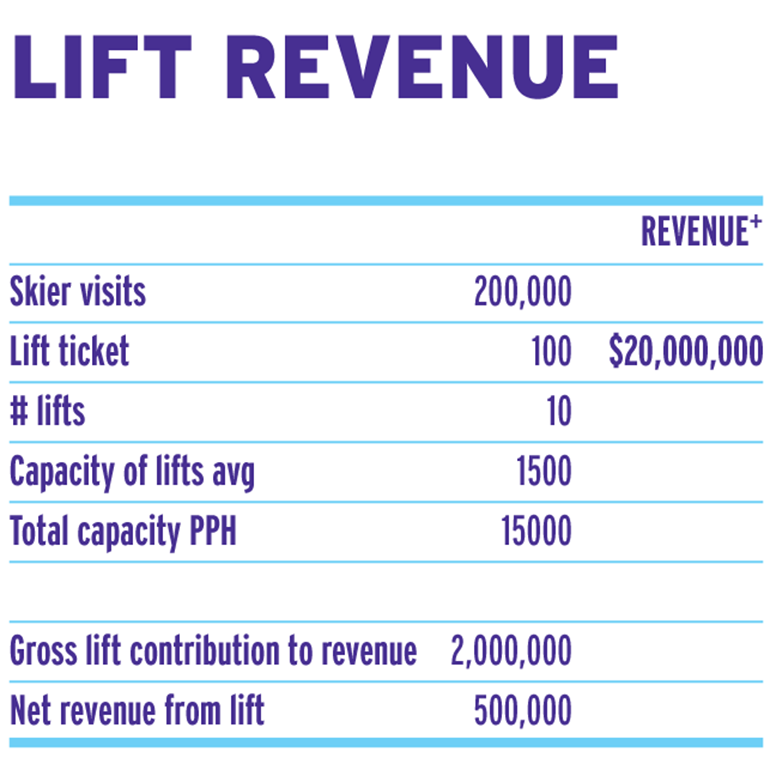

How much revenue does a lift generate? For our example here, we allocate one-tenth of the overall lift ticket revenue to each lift; after adjusting for the contribution of snowmaking and grooming, and for the lift’s share of skier/rider traffic, we allocate $500,000 of revenue annually to this one lift.

How much revenue does a lift generate? For our example here, we allocate one-tenth of the overall lift ticket revenue to each lift; after adjusting for the contribution of snowmaking and grooming, and for the lift’s share of skier/rider traffic, we allocate $500,000 of revenue annually to this one lift.

There are several key considerations with aging lifts. First, how sound is the current lift? It may be structurally and mechanically sound, but require regular maintenance to keep it that way, and a major investment may be right around the corner. Some older lifts are more reliable and less expensive to maintain than others.

Next, and most importantly, there’s the issue of reliability. Will the lift continue to operate in a reliable manner? The industry as a whole has a very safe track record, verifying that these old lifts are safe to operate, assuming that the proper maintenance is done. But will the lift operate as you need and your customers expect it to? If not, a failure could impact revenues.

Many lifts built in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s had 25-year life expectancies. Service and safety factors incorporated into these machines have extended the life cycles, and many older lifts remain perfectly serviceable. But every mechanical device and part has a life cycle. As machines age, the potential for failures increases exponentially. That increase is minor for the first 20 to 25 years, but then picks up in an ever-climbing curve. That’s why older lifts require testing and maintenance—and more of each as they get older.

Another consideration: Are there any known issues with lifts of this design and manufacturer, or with this lift in particular? Do you have the maintenance history of the lift? Qualifying what has already been will impact your decision.

For example, what is the chair swing clearance? This can limit some older designs, which have less clearance than many, more modern lifts.

Parts availability is another piece of the equation. The number of similar lifts that were built often determines parts availability and your networking ability.

Even if drive, line, braking, and control systems remain up to code, concerns about them can begin to keep managers awake at night.

Also consider the future needs and goals of the lift. If you expect to expand or increase your business, or need to increase the capacity or reliability of your lift, these goals may obsolete a double or triple completely, and dictate you upgrade to a quad.

It’s not unusual for resorts to discover that an existing lift no longer meets the circulation patterns of current customers, and a new alignment would ease traffic flow across the resort. It’s also possible that realignment or replacement of one lift will increase (or decrease) usage of others.

And finally, there are the economics to consider.

A PRACTICAL EXAMPLE

Let’s consider the case of a 30-year-old Hall lift—a triple chair, 1,800 pph, 450 fpm, 3,000 feet long, on a 750-foot vertical. The goal is to identify any critical variables, and to then evaluate the options for them. Is it feasible to retrofit the lift in stages, for example?

The variables to consider:

• capacity: will it stay the same, or increase?

• alignment: will it remain the same, or change?

• lift condition: what kind of shape are the chairs, grips, line equipment in?

• are the footings in good condition?

• what sort of records are available; have safety bulletins been addressed?

Let’s assume that the capacity and alignment remain the same; that the line equipment is generally in good condition; that NDT has been done on the grips and chairs; and that well-kept records indicate the lift has a good history of maintenance.

SHIFTING THE CURVE

The immutable law of mechanics is that as machines age, the potential for failures increases exponentially. Good maintenance can slow the climb, but not stop it.

In some cases, though, you can shift that curve by replacing key components—gearbox, drive system, motor, bullwheel bearing replacement rebuild, etc. Or perhaps you can extend a lift’s life with a new drive or return terminal, chairs, or sheave trains.

Let’s return to our prototypical Hall. It has several strengths: relatively robust design; good parts availability, due to compatibility with newer equipment or components from other suppliers; safety bulletins are available.

On the downside, there are some unavoidable issues. The low-voltage and high-voltage controls are outdated, and are now unreliable and need replacement. Gearbox parts and serviceability are problematic. The braking systems and other grandfathered systems have a narrower margin of safety than newer designs.

THE CASH FLOW APPROACH

What are the options?

Well, a new lift might cost $1.5 million. New drive and tension terminals could be a major and effective upgrade, and worth the $600,000 cost. New chairs and grips, for $300,000, might extend the useful life by 10 or 15 years.

To put some numbers to our options, consider the following options.

Option 1: Maintenance only at 30 years, with a gearbox rebuild and chair/grip replacement at 45 years, and with eventual replacement of the lift at 51 years.

Option 2: Install new drive and tension terminals at 30 years, and replace chairs/grips at 45 years, as with option 1; all other maintenance is done as necessary and required.

Option 3: Install a new lift at 30 years, followed by normal maintenance.

To determine which approach makes the most sense, look at both the revenue and costs associated with each of these over the long term—let’s say 15 to 30 years.

Let’s assume overall lift revenue doesn’t change; then, apply a certain percentage of total lift revenues to the lift in question—both its current share of revenues, and its future share.

On the cost side, for each option include the costs of yearly, five-year, 15-year, and 30-year maintenance items. For example, year 15 will include the one-year, five-year, 10-year, and 15-year items. For our purposes let’s assume the present value of money; depreciation/tax benefits have not been included. We haven’t included the cost of capital, either, but let’s assume it’s available to cover any of the three options.

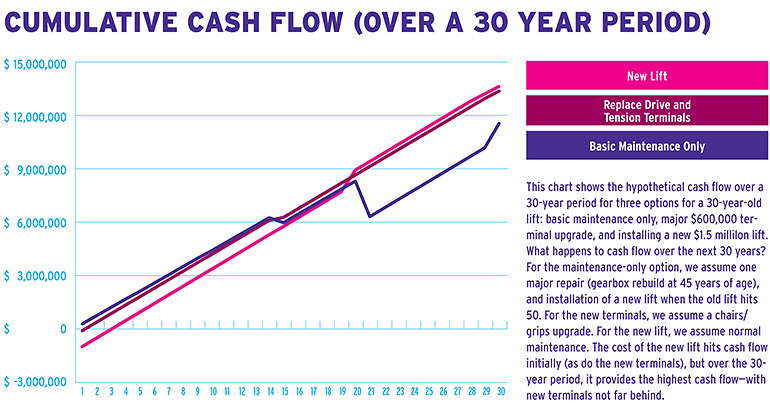

Now, the fun part: add up the revenues and costs for every year, and subtract the latter from the former to determine the total cash flow by year. (See graph. Your results may vary, of course.)

The results may be surprising.

Over the 30 years with our hypothetical lift, cash flow from option 1—maintenance only, with a major repair and eventual replacement—is nearly $11.6 million. For option 2—new drive and tension terminals at 30 years, new chairs/grips at 45 years—cash flow is $13.4 million, a $1.8 million improvement over option1. Option 3—installing a new lift, followed by normal maintenance—produces cash flow of nearly $13.7 million, about $2.1 million better than option 1, and almost $300,000 better than option 2.

CONCLUSIONS

This type of cash flow analysis enables informed decisions. For example, if you have a 30-year time horizon, the cash flow view in this case might recommend installing a new lift. It’s more costly and risky to push a 30-year-old lift for another 30 years.

If your time horizon is 15 years or less, new terminals might be the best approach. That option shifts the need for high annual maintenance costs out a decade or more, and it largely manages the liability and mechanical risks and their associated costs. Pushing a rebuilt, 30-year-old lift another 15 years or more (assuming proper maintenance) can be a good option.

Your decision-making starts with understanding the health of your existing lift and what it will take to keep it running smoothly. Factor in your time horizon, how heavily a particular lift is used or will be used in the future, and how essential it is to your overall operation. Then do the math to compare your options for simply maintaining, upgrading, or replacing it. It’s not a simple decision, but if you take the time to really understand your choices, you can make sure your decision is a smart one.