A special analysis and commentary by Andy Bigford.

The town of Nederland’s efforts to buy neighboring Eldora Mountain Resort, with the support of an advisory group called 303 Ski, might be called heroic—and a model for others to follow. The town and 303 Ski rose to the occasion after Powdr Corp. put Eldora on the market, investing more time and energy than any other suitors. The town is now on the cusp of making a massive, unprecedented investment, more than 35 times its annual budget, via high-interest municipal revenue bonds.

This could be a case study of a small mountain town rejecting the threat of a corporate takeover. In seizing control of its own future, Nederland is pledging to elevate the ski area to a new level of four-season success while leveraging this “economic driver” to also solve the difficult issues of affordable housing, childcare, and transportation. Ned is a tiny town with a big heart and a lot of moxie: It’s hard not to support the underdog in this David vs. Goliath tale.

Challenges Abound

Alas, Nederland’s ultimate success depends on using scant resources and thin knowledge to expertly lead a resort that dwarfs it in revenue, personnel, and capital-intensive challenges. Resort experts along with longtime Eldora patrons, most of whom are not town residents, reacted to the plan to buy the ski area with shock and disbelief. The skepticism hinged on these concerns:

- No clear funding exists for required capital improvements, and relying on grants or philanthropic donations is insufficient.

- The interest rates and debt are too high, particularly when coupled with the town’s idea to eventually squeeze profits to fix its own aging infrastructure. This is the old, disproven method of operating a resort on a shoestring.

- And: What happens when the next mayor and town board hate skiing? The electorate and elections are fickle beasts; just look at the state of our country. The bond issue doesn’t require a vote, but a decision of this magnitude will be voted on when the next mayor and board of trustees are elected.

As it stands, the town is in a “silent period” while it works with an underwriter to sell municipal revenue bonds to cover the $115–$120 million purchase price, a debt that will be paid off by resort revenues, not taxpayers.

October fire at the Caribou Village Shopping Center in Nederland. Credit: CBS NewsIn the interim, Nederland officials have been dealing with the aftermath of a devastating early October fire that wiped out the town’s largest shopping mall and some 20 critical businesses, which contributed almost a third of the town’s sales tax revenues (the 1980s-era building didn’t have sprinkler systems). That tragedy spurred Go Fund Me donations exceeding $400,000 for the affected businesses and rallying cries of “Ned Strong.” Rather than divert officials’ attention, the fire seemed only to redouble their efforts to purchase the resort. The town is forging ahead with a Dec. 16 finalization date (don’t be surprised if complications push it later) to buy Eldora.

October fire at the Caribou Village Shopping Center in Nederland. Credit: CBS NewsIn the interim, Nederland officials have been dealing with the aftermath of a devastating early October fire that wiped out the town’s largest shopping mall and some 20 critical businesses, which contributed almost a third of the town’s sales tax revenues (the 1980s-era building didn’t have sprinkler systems). That tragedy spurred Go Fund Me donations exceeding $400,000 for the affected businesses and rallying cries of “Ned Strong.” Rather than divert officials’ attention, the fire seemed only to redouble their efforts to purchase the resort. The town is forging ahead with a Dec. 16 finalization date (don’t be surprised if complications push it later) to buy Eldora.

The high stakes go way beyond town limits: They also involve the long-term health of the ski area, its 700 employees, and the thousands of “locals” (most of them not Nederland residents) who have loved and supported Eldora over the decades. There are the many Ikon Pass holders along the Front Range who have discovered that Eldora is a great alternative to the snarled I-70 corridor. And in the bigger picture, like most ski resorts in the West, Eldora largely operates on publicly owned U.S. Forest Service property, and that agency would have to sign off on any sale.

As everyone waits, here’s how we got here.

Ikon Success Story

Opened in January of 1963, Eldora is the place where Bob Beattie created the first unified, year-round U.S. Ski Team, and the likes of Buddy Werner, Bill Marolt and Jimmie Heuga rode the lifts. A breakthrough moment came in 1967, when owner-engineer Tell Ertl cobbled together what is essentially Colorado’s first snowmaking system.

Eldora often struggled financially, losing customers when the Eisenhower-Johnson Tunnel opened in the early 1980s and then winning them back when 1-70 became a congested mess in the early 2000s. The tri-ownership of industry heavyweights Chuck Lewis, Graham Anderson and Bill Killebrew lent Eldora a strong, steady hand for a quarter century before selling to Powdr in 2016.

Then Eldora suddenly became an overnight success. The stewardship of the new owner resolved long-simmering environmental concerns, befriended locals, and pumped some $35 million into capital improvements. The game-changing makeover included the ski area’s first high-speed lift, a major parking lot expansion, and the new beginners’ area Caribou Lodge, which is shared with the adaptive program. Now-retired president and GM Brent Tregaskis oversaw the reinvention, combining strong operational knowledge with rare people skills and a passion for the sport.

Eldora, which has always skied above its 1,400-foot vertical and 680 skiable acres, was finally ready for the big stage.

The 250,000-some Ikon Pass holders who live on the Front Range, from Colorado Springs to Fort Collins, took note of all the upgrades and soon discovered Eldora as an I-70 alternative. So did students at the University of Colorado, who were drawn by Powdr’s ever-expanding Woodward terrain park. The newcomers brought congestion through town and to the ski area on peak days, but they also provided the revenue that makes the ski area’s balance sheet so healthy. And they helped pay for the new toys, including an expanded parking lot that severely reduced traffic issues for the town and resort.

A further business upside: Access to Eldora is easy, so it draws customers for three-hour shifts, with the parking lot turning over during a typical day. Ikon “scans” count for as much as 75 percent of Eldora’s total visitors, a ratio that is either at the top of the Denver-based Alterra Mountain Company’s Ikon roster of 70 resorts, or near it. Preserving the “scan rate,” what Alterra pays Eldora for each Ikon Pass redemption, is critical to this deal.

John Cumming’s Powdr is by far the most successful owner in the history of the resort, and it’s a shame to see the company go. The resort now draws more than 400,000 skier visits, records roughly $50 million in annual revenue (swelling Ned’s sales tax collections when the skiers spend money in town) and delivers more than 20 percent in consistent EBITDA. According to the NSAA’s definition, Eldora falls between medium and large resort status. Cumming is a good businessman, but he’s also the sort of disruptor who, when other deals failed to materialize, would wholeheartedly support the town’s bootstrap efforts.

Ned’s Risky Business

Nederland has 1,500 residents, a $3.2 million general fund budget and 25 employees, fewer than Eldora’s ski patrol. It probably would have become a pricey suburb of affluent Boulder if it weren’t for the wind, which blows relentlessly at 8,235 feet. Instead, it’s become a funky hamlet for the idiosyncratic and independent minded, most of whom have collectively harbored a long reluctance to ever being called a “ski town.” Eldora is a day ski area, after all, not a destination resort.

The town government has a mediocre track record, at best, and had to shutter its police department, contracting its law enforcement to the county sheriff. Its default move is to prevent change, and residents mostly embrace that approach.

Nederland has major challenges in fixing its ancient water and sewer infrastructure, solving water supply issues, building a second bridge over Middle Boulder Creek (which bisects the town), and providing affordable housing. It has been at a long impasse to re-develop its deteriorating downtown because of friction with the polarizing owner-developer. That’s understandable—but smart, effective leadership first solves its own problems before taking on ones that are much more difficult, such as running a medium-large ski area.

“They have all kinds of ideas,” says 25-year-resident Lee Stadele, who has attended countless town board and P&Z meetings over the decades in his role as both a surveyor and concerned citizen. “The problem is they never follow through.” Other residents and employees acknowledge the risk but believe this is better than being owned by a corporation, such as Vail Resorts.

Municipal revenue bonds are a promising tool for ski towns. They are typically not used to buy ski resorts but rather for building affordable housing, hospitals, or parks. General obligation bonds are tied to a town’s assets, but revenue bonds are limited to the project being funded. The town of Vail, for example, with a robust $132 million annual budget for 2026, just successfully issued $126 million in municipal revenue bonds, with a 30- to 40-year term, at around 5 percent. These will go to build 268 units of much-needed employee housing; there was high demand for the bonds, but the funding tool was still considered risky and the town will pay an estimated $366 million in interest.

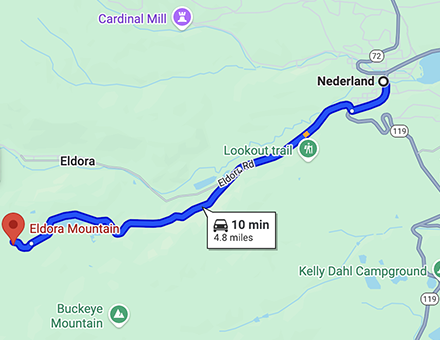

The map shows the distance between Eldora and Nederland.Many of the safest municipal bonds sell for around 4 percent. Little is known about Nederland’s bonds, but the high-risk nature is reflected in its own projection of a “6-8 percent” annual interest rate. These are more commonly known as “junk bonds.”

The map shows the distance between Eldora and Nederland.Many of the safest municipal bonds sell for around 4 percent. Little is known about Nederland’s bonds, but the high-risk nature is reflected in its own projection of a “6-8 percent” annual interest rate. These are more commonly known as “junk bonds.”

The final bond rating and its interest rate will be critical to watch, as will the term, which could be just 10 years. The fire that destroyed 30 percent of the sales tax base seemingly won’t help. The bonds will be sold to large institutional investors, not powder-obsessed, Eldora-loving locals with some spare cash, and these bondholders will have a say in resort operations if they don’t get their money on schedule. They would also control the resort if there were a default on the bonds.

Powdr searched high and low for an experienced operator, but nobody could meet its price. (With Alterra and Vail Resorts absent from the bidding for various reasons, this almost-two-year process revealed a buyer’s, not seller’s, market.) The town lacked experience but made up for it with staying power—and by being the last suitor standing and willing to pay. Many Nederland residents publicly embraced the basic concept of taking control of the ski area and their future, theoretically at no taxpayer cost, and the town did a good job of brainstorming and then, at least initially, communicating its mission.

Many Eldora patrons, meanwhile, wanted the ski area to go to an experienced operator with resort savvy and the capital to invest. This created a first-ever divide among Eldora loyalists: Those who are Nederland residents and the majority who are not. While almost everyone drives through this funky town on the way to Eldora, less than 10 percent of the resort’s employees and customers are Nederland residents. The stakeholders come from elsewhere, and it’s always been known as “Boulder County’s ski area.”

303 Ski

But there was also guarded optimism that high-level expertise would drive the effort. This came largely from the involvement of 303 Ski, a local group led by Nederland General Store owner Dwight DeBroux, who had been a Vail Resorts retail manager. The group partnered with the town to provide operations advice and business direction after it was unable to meet the purchase price itself.

There’s been good advice from 303 Ski, and it includes smart, well-meaning ski industry veterans. But it’s alarming to note that the only advisory board member with actual ski area operations and acquisition experience has resigned.

Blaise Carrig is the former Vail Resorts mountain division president who attributes his success, and his career, to falling in love with the sport at a small community ski area in upstate New York. He has a soft spot for small hills, having made personal and financial commitments to support Wyoming’s Antelope Butte and its community-driven, nonprofit startup. Beginning his career as a patroller, he ascended to oversee major resorts in the East and West, and then to steward Vail Resorts’ various mountains and acquisitions.

Carrig’s unrivaled experience was never sought or tapped, though, and he has since quietly stepped away from 303 Ski.

As Powdr and the town remain mum through the underwriting process, looming in the background is the need to replace GM Tregaskis. Eldora opened for the 2025-26 season last weekend. The dedicated staff can operate the ski area just fine, but Eldora needs someone who can also become a respected conduit and public face through what is likely to be a challenging transition.

Ungroomed Terrain Ahead

Powdr invested heavily in Eldora, including a parking lot expansion to help alleviate traffic woes.When the town completes the purchase, the real challenges begin. The resort’s ability to compete in the hyper-competitive Colorado market will be restrained by an indebted municipal ownership whose first charge should be to provide services to the town, as it’s admirably doing now in the aftermath of the fire.

Powdr invested heavily in Eldora, including a parking lot expansion to help alleviate traffic woes.When the town completes the purchase, the real challenges begin. The resort’s ability to compete in the hyper-competitive Colorado market will be restrained by an indebted municipal ownership whose first charge should be to provide services to the town, as it’s admirably doing now in the aftermath of the fire.

The town’s leaders want to add summer operations and bring back night skiing at Eldora, both of which would require significant capital investment and an uphill slog of regulatory approvals, including overcoming wildlife concerns. Summer ops could boost Nederland’s four-season appeal but are unlikely to generate substantial revenue.

This all feeds into to the biggest concern of all:

How would the town, with its cumbersome junk-bond debt payments coupled with a long- term hope to use resort profits to repair sidewalks, fund these projects as well as other necessary capital improvements in the near- and long-term? Old lifts will need to be replaced or overhauled, snowmaking infrastructure upgraded, new facilities built—not to mention building a new lift to serve the approved Jolly Jug terrain expansion. Powdr spent some $35 million in its nine-year tenure to upgrade the resort; is Nederland prepared to invest that amount, or at least three-quarters of it?

The town has begun the job of planning with a $10 million “rainy day” fund to cover downturns and $2 million annual tab for routine maintenance included in its bond offering, but most of the tough questions remain unanswered.

Annexation of the resort, which is now in unincorporated Boulder County, could swell the town’s sales tax coffers by $2 million annually. But this brings its own challenges and costs, including maintaining and plowing the mountainous Shelf Road that leads to Eldora, and presumably providing law enforcement.

Overall, the ownership model seems too reminiscent of the past, when cash-strapped owners borrowed money to get through the down times and didn’t have the funds to invest in improvements.

Will it all work out in the end? Only time will tell.

Final Thoughts

In the meantime, here’s some unsolicited advice:

If Powdr will run the ski area for two seasons during the transition, as the town indicates, jump on that agreement now. Use the time to get up to speed and determine a plan.

Then find a professional operator and get out of the way. There are many ways to accomplish this; finding an equity partner who can fund improvements is a good one.

Isolate the resort from any political winds blowing in Nederland. Understand that your fate, from the residents to town hall, is now tied to the resort.

Beware the pitfalls: Gunstock is a New Hampshire ski area that shares similarities with Eldora, including 1,400 feet of vertical and a nearby college. It is government-owned, in this case by Belknap County. In 2022, its top five managers, led by veteran GM Tom Day, resigned after a county oversight board continually meddled in their daily ops and dismissed their professional opinions. This was all reversed in the outcry, and the resort has followed its management’s successful vision, but there’s a lesson to be learned in the overreach.

“A few folks have said we’re crazy to do this,” says Nederland Mayor Bill Giblin. “I say we’d be crazy not to.”

Virtually everyone wants to see the town, the ski area and its stakeholders succeed, and for Powdr to get a fair return on its investment. Is this the way to ensure that Eldora not only survives but thrives? Or will it set a poor precedent for municipal ownership of ski areas?

We are about to find out, and the repercussions go way beyond town limits. The ski world will be watching.

Andy Bigford has lived in Boulder County for 28 years and estimates he’s skied at Eldora more than 600 times. He’s a former newspaper editor in Breckenridge and Aspen and was the editor-in-chief of SKI magazine. He has edited or written six books, and was the co-author of Eldora: Six Decades of Adventure.