In the past decade, mountain biking’s growing popularity has pushed many ski areas to add it to their roster of summer activities. Yet, while some bike parks flourish, others quickly peter out, with resort operators citing high costs, lack of interest, and a low return on investment.

According to several ski area bike park operators and consultants, there are some clear make-or-break considerations that can lead to a park’s success or failure.

A Growing Community

In 2019, the realignment of a popular mountain biking trail near the center of North Conway sparked a new age of trail development in New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Valley.

Many of the new trails were constructed on Cranmore Mountain Resort’s property. These were hand built, with some machine-built sections, by local organization Ride NoCo and the White Mountain chapter of the New England Mountain Bike Association (NEMBA). When the trails began garnering the attention of New England riders, the timing couldn’t have been better for Cranmore, says general manager Ben Wilcox.

“North Conway is a busy summer destination, and we already had established summer activities,” he says. “But our aerial park was flattening out on business. And right before we decided to get into mountain biking [in 2020], North Conway was becoming a mountain bike destination because of the work Ride NoCo and White Mountain NEMBA were doing.”

Between the influx of mountain bikers flocking to North Conway to ride the new trails and the riding options Cranmore guests would have beyond the resort, Cranmore was poised for success.

Strong Demand

Like Cranmore, British Columbia’s Sun Peaks has found success in part due to its proximity to popular trails and an existing mountain biking community, both of which were major motivating factors for expanding the resort’s trail system in 2019.

“Mountain biking was experiencing a huge increase in new participation,” says Sun Peaks director of communications Christina Antoniak.

As the local cross-country trail networks grew, attracting more riders to the area, the resort expanded its bike park, providing options for those who wanted to ride lift-accessed trails, too. “We invested around $350,000 into machine-built trails in 2019 and $1.5 million in opening a second mountain for biking in 2022,” says Antoniak.

Left to Right: Berkshire East, Mass., knows expert trails and riders add marketing value (Credit: Katie Lozancich); Cranmore, N.H., has one lift dedicated to mountain biking (above) and another for scenic lift rides, which benefits the guest experience and operations (Credit: Josh Bogardus).

Left to Right: Berkshire East, Mass., knows expert trails and riders add marketing value (Credit: Katie Lozancich); Cranmore, N.H., has one lift dedicated to mountain biking (above) and another for scenic lift rides, which benefits the guest experience and operations (Credit: Josh Bogardus).

Other Elements

While having a thriving mountain biking community and a renowned local trail network can significantly improve a ski area’s chances of success, they are only part of the equation.

According to Dave Kelly, founder and director of mountain bike trail-building and consulting company Gravity Logic, other key factors to consider include the physical terrain, existing infrastructure, and a ski area’s proximity to a significant urban population.

Physical Terrain

A successful bike park requires terrain conducive to mountain biking. Just because terrain is skiable doesn’t mean it’s bikeable. “Sometimes I’ll go look at a ski area and it’s just way too steep or narrow,” says Kelly.

“We don’t put mountain bike trails on ski runs,” he adds, as that affects winter operations (think of the extra snow coverage needed to cover a four-foot berm cutting across a piste), and the trails would take more of a beating from the elements.

Trails on mountains with steeper terrain, like Oregon’s Mt. Hood Skibowl, are more challenging to maintain and expensive to build, and can be dangerous to ride. Also, steeper trails exclude beginner riders—a significant segment of the market.

“It’s not that you can’t invest in it, but it costs a lot of money to build trails on that kind of terrain,” says Skibowl vice president and general manager Mike Quinn.

For Skibowl, steep terrain was one of several factors that led to the bike park’s 2022 closure. A significant bike-injury lawsuit, which resulted in an $11.4 million verdict, was another.

Existing Infrastructure and Operations

Skibowl’s chairlifts—all fixed-grip doubles—didn’t do it any favors, either.

“[Mountain biking] was in conflict with our alpine slide operation because they shared a fixed-grip double chair,” says Quinn. Logistically, segregating foot and bike traffic on a single fixed-grip lift, and transporting bikes, is difficult. Having a high-speed quad or six-pack chairlift dedicated for bike use simplifies the flow of traffic at a resort.

Yet another complication at Skibowl: “When we got into the wedding business, there were conflicts of people mountain biking around the wedding venue,” Quinn says.

One Piece of the Puzzle

As Skibowl learned, it’s essential to consider how (and if) mountain biking will complement other summer operations.

“The most successful mountain resorts are looking at a package of experiences for guests to participate in,” says Rob McSkimming, mountain resort development advisor at Select Contracts. “Not everyone wants to participate in mountain biking, so the more well-rounded the activities, the better.”

Bike park products and services, such as rentals, lessons, camps, and women’s programs can add significant revenue. At Cranmore, says Wilcox, “I think if we didn’t have the rental business, the bike park wouldn’t be as successful. Our whole model is based on how many bikes we rent and how many lift tickets we sell.”

Rentals allow newer riders (or those without a full downhill set up) to try the sport, potentially creating more dedicated mountain bikers in the future. Rentals also allow guests to ride on the local recreation path, which cuts through town and links the resort with several cross-country trail networks.

Such offerings are often under-prioritized, says McSkimming. With these, particularly programming, he says, “The opportunity is there to not get entirely focused on the trail experience, but also to be able to provide customer engagement, growth, and development.”

A hardworking trail crew diligently maintains that investment all season long (Credit: Katie Lozancich).

A hardworking trail crew diligently maintains that investment all season long (Credit: Katie Lozancich).

Fully Commit

If mountain biking is feasible and will complement existing activities, the do-or-die decision is whether a resort is willing to invest enough time and capital to build a diverse network of trails out of the gate.

“If a ski area wants to stick their big toe in the water to see if it’s warm enough, they’re going to fail,” says Kelly. “They have to believe in the product and jump all-in with that capital and be committed to it.” Capital plan failures, he says, are one of the major reasons MTB parks collapse.

After factoring in increased lift depreciation from operating year-round, operating costs, and potential costs associated with risk and liability, says Kelly, there’s no point in starting small. Even smaller resorts likely have to invest upwards of a million dollars to succeed, he says.

Risk and Reward

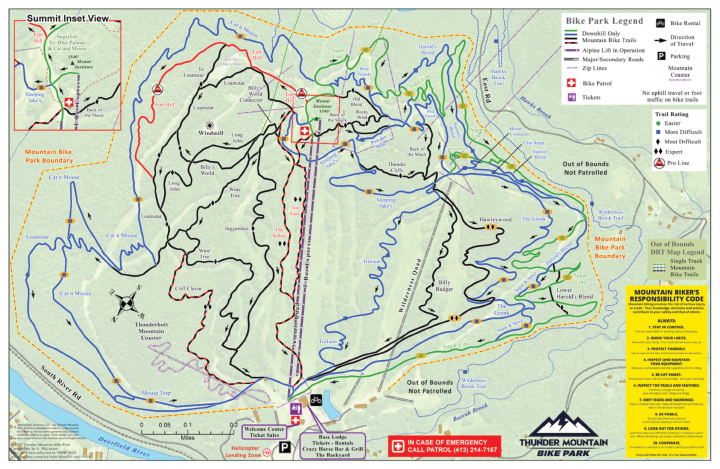

Investing that kind of capital is a considerable risk for smaller resorts, but the reward has been worth it at Massachusetts’ Berkshire East, which rebrands as Thunder Mountain Bike Park in summer.

“There wasn’t really a downhill mountain biking scene in our area,” says Berkshire East owner Jon Schaefer. Over the years, he watched many ski areas start small and fail.

“We went all-in and built [the park] really big and fast,” he says. “Our goal was to build brand awareness that would carry for a decade or more, and make it difficult for other mountains to catch up to us.”

So far, the decision to invest just over a million dollars in the bike park, which has now operated for more than a decade, has paid off—and not just in revenue.

“Mountain biking truly converted us to a year-round operation, and that allowed us to retain key staff,” says Schaefer. “We couldn’t retain staff when we were just doing a few zip lines. So it added a lot to the entire mountain and provided momentum from a branding standpoint about who we are.”

Trail Design and Diversity

Like skiing, a successful mountain bike park has to offer terrain diverse enough to engage riders of all abilities, with most of the focus on intermediate trails. Typically, beginners learn quickly, eliminating the need to build many novice trails. But a range of intermediate flow trails will keep even expert riders busy.

“Essentially, you need one green trail to start because people progress pretty quickly, or maybe they’re only there for one day,” says McSkimming. “But you need to be smart about that trail because it uses a lot of terrain.

“Then you’ll want a few intermediate options, including at least one excellent jump trail. And over time, you might want to add more advanced trails.”

It’s important to provide a few good machine-built flow trails, McSkimming says, as riders typically will not find that experience outside of a bike park; lower-budget hand-built trails are the common fare in community networks.

He also notes that an area’s demographic informs decisions about what types of trails to build, and at what point to build them. For example, a mountain like Sun Peaks that boasts a dedicated mountain bike community might want to add a few extra challenging trails during the initial roll-out of a new bike park, rather than waiting to add them at a later phase.

Trail networks benefit from a mix of flow trails, like this steep one at Sun Peaks, B.C. (Credit: Reuben Krabbe)

Trail networks benefit from a mix of flow trails, like this steep one at Sun Peaks, B.C. (Credit: Reuben Krabbe)

Marketing Value

Kelly notes that in places with dedicated riders, the more difficult trails—and those who ride them—often add marketing value. “You need to offer trails that progress to double black diamond and above, so you can attract core riders who are often the most vocal,” he says. “They promote your product on social media.

“Word-of-mouth marketing is still really big in mountain biking.”

Trail Maintenance

Once built, a bike park requires maintenance. Without it, a park can lose momentum fast. To instill an understanding of what’s involved, says Kelly, Gravity Logic likes to involve the resort’s staff in the construction process.

While much of a trail’s resilience to erosion comes down to proper design, constant trail maintenance is also a factor.

“It’s sort of like grooming at a ski area,” he explains. “When you know a ski area has good grooming, you go and say, ‘every time I’m here, the grooming is awesome—I love this place.’”

Conversely, riders lose interest when trails get washed out and holes develop, and there’s more potential for injuries.

According to Kelly, a resort should have a dedicated trail crew with at least one excavator. And while the cost can vary, an operator should budget for roughly 10 percent of the capital that was invested into the bike park for maintenance annually.

Considering Loss

Even well maintained, managed, and designed trails can sometimes lead to injuries and lawsuits, making the risk versus reward analysis important to consider.

Tim Hendrickson, senior vice president and program manager for ski area insurance program MountainGuard, says there are several factors that affect the cost of insurance.

“We get an idea of the general layout of what they want to do, what they’re looking to build, the number of trails, whether or not there’s lift access, progression, and if there will be manmade features,” says Hendrickson. Jumps, which can increase risk, also play a role. “But our quote is really going to be based on how many people are doing the activity,” he adds.

Berkshire East, Mass., invested in a robust and diverse trail network right from the start.

Berkshire East, Mass., invested in a robust and diverse trail network right from the start.

Return on Investment

With the number of factors that play into profitability, a reasonable return on investment varies significantly between resorts. That said, a three- to five-year ROI is about average for many ski areas, according to Kelly.

“We may forecast a ROI period greater than [that], and some resorts decide to put their capital elsewhere,” says Kelly. “But some calculate their own returns based on revenue outside our proforma, such as food and beverage and accommodations. Others calculate in human factors, like staff retention.”

The same can be said about the time it takes to establish a bike park brand. Kelly notes that some brands find success quickly, while others, even well-built trail networks, struggle, often due to poor marketing.

Kelly cited two to four years as a reasonable expectation, and “three to five years of solid capital and marketing effort for a park to establish itself in the ranks of Trestle, Killington, Deer Valley, and Thunder (Berkshire East).”

The TLDR

Despite the additional cost and risk, mountain biking can be a significant revenue generator and a key component of a resort’s summer offerings. If a resort has the necessary physical terrain, available infrastructure, and proximity to a populated area—or at least two of these three attributes—the elements of success are in place. As long as the proper investment is made and operations are thoughtfully managed, the transition from skiing to mountain biking once the trails dry out each spring can be seamless.

“Biking is an amazing revenue generator that has the ability to save these small- and medium-sized resorts from bankruptcy,” Kelly says. “But it has to be done right.”