Paul Mathews launched Ecosign in 1975 with a one-dollar business license and an idea: that ski resorts could be designed using a comprehensive and systematic process. Fifty years and more than 1,000 projects later, his firm has helped shape mountain resort development across 46 countries, from British Columbia’s Whistler Blackcomb to Sochi, Russia.

Ecosign celebrated its 50th anniversary this year. To ensure its longevity into the future, Mathews transitioned the firm to employee ownership, remaining at the helm as chairman and CEO. As he contemplates retirement, SAM spoke with Mathews about his early days, his design philosophy, and the future of ski resort planning.

You learned to ski as a young kid on a rope tow in Breckenridge, Colo. Why do you think the sport stuck?

Well, first, I was doing it with my family. We had to go up over Loveland Pass (before the construction of the Eisenhower Tunnel), and there was a little rope tow behind the county courthouse in downtown Breckenridge. It’s still there. It only ran on weekends, and they had the kids all sidestep down to pack the snow on the slope—so, I guess I was a groomer at a young age.

I’ve always loved skiing. It’s been in my blood for 78 years now. The fresh air. All of it.

What inspired you to start Ecosign?

I graduated from university in 1974. I couldn’t get a job, so I bought a business license for a dollar and got it started. That was over 1,000 projects ago.

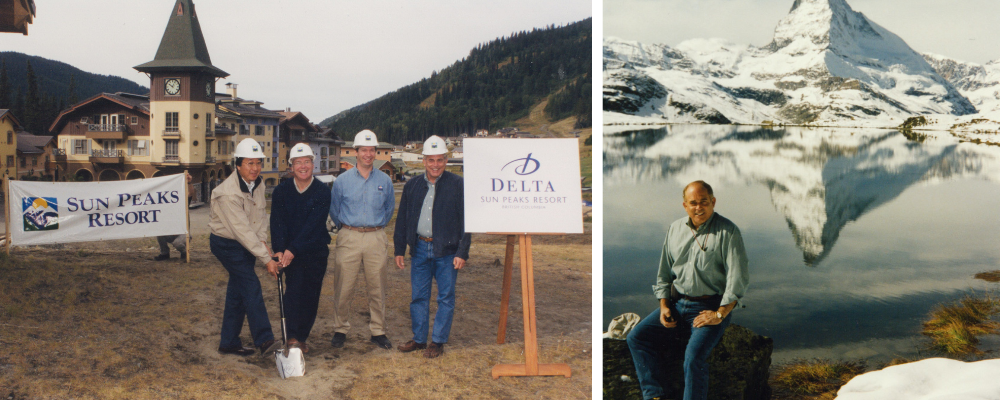

Left to right: Groundbreaking for the Delta Sun Peaks Resort (now the Sun Peaks Grand Hotel and Conference Centre) in summer 1998. Left to right: Masayoshi Ohkubo, then-owner of Sun Peaks; John Johnston, president of Delta Hotels; Darcy Alexander, CEO, Sun Peaks; and Paul; Paul in Zermatt at Lake Stillisee, summer of 1998, framed by the Matterhorn.

Left to right: Groundbreaking for the Delta Sun Peaks Resort (now the Sun Peaks Grand Hotel and Conference Centre) in summer 1998. Left to right: Masayoshi Ohkubo, then-owner of Sun Peaks; John Johnston, president of Delta Hotels; Darcy Alexander, CEO, Sun Peaks; and Paul; Paul in Zermatt at Lake Stillisee, summer of 1998, framed by the Matterhorn.

What sparked your vision as a teenager to become a ski area designer?

I was skiing at Whistler Mountain, and they were just making a mess of the ski runs, cutting and leaving stumps two meters high. It wasn’t … planned. It made no sense to me. So, I thought I should study and learn about nature—the birds, bees, and trees—and study hydrology, and learn how to build responsible, sustainable ski runs and ski resorts.

I also saw that there’s a long system you’ve got to go through to go skiing: You’ve got to get there, find parking, find the place you’re staying or booting up. So, I knew I wanted to learn how to create a whole resort.

Describe your views on resort planning and environmental sustainability.

If you’re going to do a development, nature is going to pay a price. I guess the question is: What kind of price? What we like to do, when we start a new resort, for example, is document all the natural resources—water, wetland, habitat for species—and then we just basically try to avoid those areas. We won’t touch them.

We are also very big proponents of having a high-density central area that is within walking and skiing distance of the lifts. That reduces all the transportation requirements. Like at Whistler now—we have about 70,000 total beds, and about half of the guest beds are ski in/ski out. That means you don’t need a car here.

When Whistler first opened [the municipality was incorporated in 1975], I think 90 to 95 percent of people arriving by plane rented a car and drove up. Now, [45 percent of destination visitors] come by bus. We actually have too much parking underground, because people aren’t using it anymore.

How receptive have developers been to your vision of dense planning?

Real estate at mountain resorts has historically been—and in the United States still is—just horrible. They just want to sell the dirt and get rid of it. We have been very hard pressed to push public beds (i.e., hotels and such type lodging). When you just have the single-family cabin that is used 28 days a year, there’s just no business out of that for the operator because you have two peak days a week over a four-month season, so you have 40 days of business. But you need 150.

[With group lodging], they get breakfast, lunch, and dinner revenue. They get revenue from lift tickets, the ski school, all of it. So, every hot bed kicks out, oh, I don’t know, $150 to $200 a day per pillow. It’s good business to have warm beds near the lift. And as I said before, then you don’t need the bus systems, the parking lots, and all that kind of stuff.

Peak 2 Peak at Whistler is a signature Ecosign project. What inspired it?

I designed Blackcomb Mountain back in the late ‘70s, and I’d always thought about trying to connect the mountains. But we were always just thinking of going down into the valley and then going back up for the connection. That’s just not very exciting, you know?

Then in 1997, I think it was, I was in Europe with Hugh Smythe, the president of Intrawest [which owned Whistler Blackcomb at the time]. We were in Zermatt, where they hired a helicopter to show us around. We were headed toward the Matterhorn, and we could see a silver line going up to the smaller, hiking Matterhorn. [The Klein, i.e. Little, Matterhorn is a popular starting point for hiking tours.]

Smythe said, “What is that?” and I said, “That’s an aerial tramway going up to the small Matterhorn.” He said, “Well, how long is it?” I told him, “It’s about 2.6 kilometers,” which is about the same distance from Blackcomb to Whistler, and he went, “Oh my god, are you kidding? Do you think we could do something like that?” I said, “I’d love to.”

But at that time, we were looking at [a two-cabin system]. That meant maybe 1,000 customers per hour. It just wasn’t feasible. We’d have huge lines and a lot of unhappy people. We were doing 20,000 visitors a day at that time.

Then in 2005, I was in Austria, and I saw this three-rope system, which had a cabin leaving every 28 seconds. With that, we found out we could go from the Roundhouse on Whistler to the Rendezvous Restaurant on Blackcomb in just about 11 minutes at about 2,800 people per hour. That was quite reasonable. That meant with 20,000 customers a day, we could take half of them, easily.

Left to right: Beijing Olympic freestyle venue presentation, 2017; Paul Mathews and friends summer skiing on Black Tusk Glacier, near Whistler Blackcomb, British Columbia, circa 1974.

Left to right: Beijing Olympic freestyle venue presentation, 2017; Paul Mathews and friends summer skiing on Black Tusk Glacier, near Whistler Blackcomb, British Columbia, circa 1974.

How has it aged?

The impact has been tremendous. I think we are doing 300,000 to 400,000 more visits per year because of Peak 2 Peak. That’s winter and summer. The Peak 2 Peak completely made summer. Before this, summer was a bit of an afterthought. We were doing maybe 60,000 a summer, and now we’re doing 450,000, I think—so, a big change. It worked.

You’ve designed several Olympic venues. How did that work come about?

We started in like '81 or '82. Calgary had won the '88 Olympics, and they were going into the wilderness area and developing three different mountains for three events just to host the Games. The Alberta government asked me to see if we could find one place that could host all of the Olympic Alpine venues, plus be a feasible and financially-viable recreational ski area afterwards.

That led to nearly six months of work, looking everywhere from the U.S.–Alberta border all the way up to Banff, and we found Mount Allan (Nakiska). We started designing it, working with FIS, and we found routes for the men’s and ladies’ downhills and also the technical events, and we built them.

They hosted the Games successfully, and that’s quite a viable ski operation now.

We worked on the 2002 Olympics at Snowbasin (Utah), and then for Whistler in 2010, we needed no new design. In 2005, I was designing a new ski resort in Russia, and [the head of the Russian Olympic committee and the Russian minister for sport] asked us if we could design it so they could host the Olympic Games in 2014. I said, yes. Then, for 2018, in Korea (Pyeongchang), we did the freestyle venues. For 2022, we got the job in China (Beijing) as well.

Are there commonalities for ski resorts worldwide that transcend culture? Are there idiosyncrasies?

Well, gravity is pretty consistent around the world, so that part is always the same. Generally, you go up the mountain on a mechanical lift and ski down a trail that’s been groomed.

But the base areas and villages are quite different. The base area arrangements—parking and transportation and all that—are a cultural thing; it’s unique to each spot.

For instance, skiing in Japan is having a huge resurgence. So, in resort planning, you keep in mind how people dine, how they get there. We work to learn and understand those needs.

Over 50 years, what’s the biggest change you’ve seen, and what remains the same?

The biggest change is high-speed lifts. With lift capacity up, now we’re doing 3,000 to 3,600 passengers an hour. That’s a huge change from double chairs at 1,200 an hour.

I also like very much the trend of having warm beds in the resort village at the base instead of real estate and cabins. In Finland and other spots, they were building cabins; that required building roads and sewer and water lines everywhere, all for little lots. Ski areas had huge parking and transportation issues. We got them to stop that and to focus everything into a pedestrian court with underground parking. They refused at first, saying they could not afford underground parking, but we showed them that they cannot afford not to have it. You’ve got to do it.

But the same? Ski runs are pretty much the same. That hasn’t changed dramatically as far as I can see.

How do you see resort planning evolving over the next 50 years?

I doubt we will see as many new resorts as we had in the last 50. The good sites have been chosen, so there’s not so many around. And then to get through the bureaucracy we have is complicated and expensive, so I think we will just see the evolution of existing resorts. We’re on the second and third remakes of different resorts.

Left: Sierra Nevada, Spain, site inspection, 2002. Eduardo Valenzuela, mountain manager; Mariano Gutierrez, CEO; Paul Mathews, Ecosign; Hans Timmerman, mountain operations director. Right: Paul at the Ecosign office drafting table, 1985.

Left: Sierra Nevada, Spain, site inspection, 2002. Eduardo Valenzuela, mountain manager; Mariano Gutierrez, CEO; Paul Mathews, Ecosign; Hans Timmerman, mountain operations director. Right: Paul at the Ecosign office drafting table, 1985.

Your support of smaller areas, often at deep discounts, has helped more than 30 ski areas. Tell us about it.

It’s just giving back. We can do it, you know? The cost for us is not so high, and it’s not real dollars, it’s just staff time—often me doing it myself. We get these small areas set up so they are going in the right direction, so that when they start growing, they can continue that growth.

The smaller ski area is usually the one that is closer to where people live, and that gives the whole population access. And if they like it, then they will go take that longer trip to Whistler or somewhere once a year.

What’s your favorite spot on a mountain?

For me, very often it is just a viewpoint somewhere. I like Sun Peaks Resort (B.C.) very much. If I had a role model, [Sun Peaks founder] Al Raine would be it.

Knowing what you know now, what advice would you give that little boy on the Breckenridge rope tow?

I’d say, “go to school and move to the mountains,” which is exactly what he did. To have worked in 46 countries on over 1,000 projects? It’s been a very good ride.