For years, adaptive programs have opened the slopes to people who thought the sport was out of reach. Now, many resorts are reimagining their entire guest experience through a wider accessibility lens and going beyond ADA compliance to put a premium on inclusion.

They’re asking people who use wheelchairs to take them through a day around the resort to experience first-hand where challenges exist. They’re training staff to recognize invisible disabilities. They’re creating quiet zones, low-sensory rooms, and high-vis signage.

Why? Of course, driving new business is a top priority. But the motive extends beyond boosting the bottom line, says longtime industry leader and Sundance Resort investor Bill Jensen. “Skiing,” he says, “is healing. And it can and should be healing for all.”

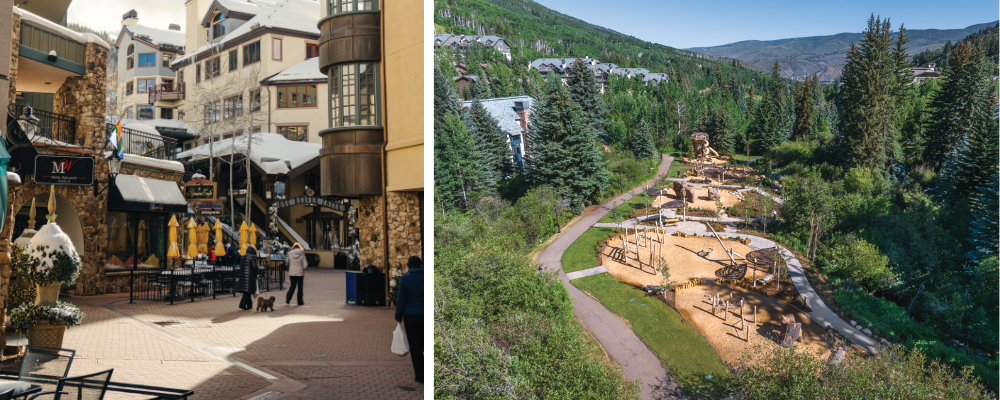

Left to right: Beaver Creek's village is in line for future accessibility improvements; Beaver Creek’s accessible, level-grade, meandering paths at Creekside Park.

Left to right: Beaver Creek's village is in line for future accessibility improvements; Beaver Creek’s accessible, level-grade, meandering paths at Creekside Park.

Beaver Creek: Guest Walkthrough Reinforces Master Plan

Last year, Colorado’s Beaver Creek launched a project aimed at overhauling the resort’s accessibility long term.

The effort started with asking a long-time loyal ski family with a child who uses a wheelchair to show resort leaders how they navigate the resort village. “They were willing to share the challenges they face to get their son around,” says director of economic development Clint Huber. “It’s fair to say that the walk was eye-opening.”

The “big” challenges—like not enough easy-to-roll-on surfaces and ramps—were not a surprise. What was, says Huber, were the little things that become big things in the world of access: elevator button heights, signage placement, trash cans blocking pathways. “As an able-bodied person, we see things differently,” he says. “It’s the humanization of things that makes a difference.”

In 2024, Beaver Creek paired $20,000 of its own capital with a sponsorship awarded through the Colorado Tourism Office’s inaugural Accessible Travel Program, which named Beaver Creek one of just three destinations statewide to receive support. The program allowed the resort to bring in Wheel the World, a global accessible travel platform, to conduct a full audit of 23 sites across the village—lodging, restaurants, retail, and activities like the snowcat sleigh ride to Beano’s Cabin. Each site was measured and documented, and all 23 earned “Destination Verified” seals, meaning guests are now able to find vetted accessibility details (like photos and bed heights) on Wheel the World’s booking platform.

From that audit, the resort created a multi-year accessibility master plan, part of its broader Inspire Vision 2030 strategy to modernize the entire village. The approach works in two phases: first, quick wins and communication improvements; second, bigger long-term upgrades. “There are a lot of simple things we can do to accommodate more and give people a sense of belonging now,” says Huber.

Some of those simple things are already in place. Trash cans were moved away from elevator buttons so a person does not have to reach over obstacles to push buttons. Door openers were relocated so guests don’t have to go forward and then backtrack to use them. Furniture was rearranged. New projects like Creekside Park incorporate accessible paths. There are plans to train staff how to help a guest in a wheelchair board the sleigh to Beano’s Cabin “in a way that’s relaxed, comfortable, and drama-free,” says Huber.

Next steps already underway include improved signage and additional training for resort employees. Beaver Creek is also looking to improve accessibility information on its website so guests can preview accessible routes before they arrive.

The longer-term goal is to work with Beaver Creek’s many independent lodging and business partners to upgrade ramps, doors, and other infrastructure so that “mobility impaired guests will have the same experiences as all,” says Huber. That, he admits, “could be a major challenge.” But then again, what in this industry isn’t?

Mt. Hood Meadows, Ore, went beyond its adaptive program (left) and adopted the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower system (lanyard, right), which alerts staff to persons they should treat with extra care.

Mt. Hood Meadows, Ore, went beyond its adaptive program (left) and adopted the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower system (lanyard, right), which alerts staff to persons they should treat with extra care.

Mt. Hood Meadows: Hidden Disabilities Sunflower Program

Oregon’s Mt. Hood Meadows has long embraced inclusion through its adaptive ski and snowboard program. Five years ago, the resort extended that effort by forming a DEI committee, commissioning a professional audit, and creating a standing committee to guide implementation.

One early realization: many challenges are invisible. From feeling the effects of cancer treatments to mental health conditions, says DEI coordinator Madison Canfield, “You cannot know and understand what a person needs just with your eyes. We make a lot of assumptions.”

Meadows, she says, needed a way to “see” what isn’t easy to see. Enter: The Hidden Disabilities Sunflower program, a system widely used in airports and stadiums, and now at Meadows.

Guests who want to self-identify can pick up a sunflower lanyard at customer service. Staff across departments are trained to recognize the lanyard and respond to guests wearing it with patience and empathy.

Participants don’t need to disclose their specific condition, and staff cannot ask. Instead, training focuses on picking up cues and offering support in a kind, judgment-free way. “It reminds us to slow down and find out how to really help,” Canfield says.

Meadows has more accessibility and inclusivity improvements in the pipeline, too. Feedback from adaptive participants, staff, and local advocates is informing upgrades such as high-contrast paint on ledges, more comfortable seating for guests with chronic pain, and braille signage.

“We are up to date legally,” Canfield says, “but we want to go above and beyond. It’s not enough to just be ‘up to code.’ Our motto is ‘Your mountain home.’ And ‘your’ means every one of us.”

Crystal Mountain, Mich., gained Certified Autism Center status after taking a series of steps to accommodate people with sensory sensitivities.

Crystal Mountain, Mich., gained Certified Autism Center status after taking a series of steps to accommodate people with sensory sensitivities.

Crystal Mountain: Autism-Certified Resort

At Crystal Mountain, Mich., inclusion is tied directly to the resort’s values. “One of our core values is fun, and something we teach our staff from day one is that means fun for everyone,” says SVP of human resources Jennifer King. That belief, combined with a local effort, inspired the resort to pursue Certified Autism Center status.

Traverse City Tourism encouraged Crystal and other local businesses to go through the certification process, helping the region achieve a Certified Autism Destination designation in 2024. Crystal’s journey began with a multi-day audit by the International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards, which reviewed everything from guest rooms to activities. The audit produced a detailed “sensory guide” showing how different spaces might affect guests with sensory sensitivities, rating noise, lighting, and overall stimulation on a 1-to-10 scale.

It also suggested adaptations Crystal could undertake to be more friendly to guests with autism, such as the creation of a low sensory area—a room where a family can go to find quiet, adjusted lighting, and a sense of peace when needed—which the resort now has.

The process also included training, starting with King, who completed an eight-hour training that was “tough,” she says. “It was way more than I expected.” The effort was worth it. King’s experience equipped her to add education about sensory sensitivities to Crystal’s existing guest service training, which all staff are required to take. They can choose to do it in person or online and must pass a quiz before they start working at the resort.

The program is having a positive impact on the guest experience. For example, the July employee of the month, a young staffer working the alpine slide, was able to recognize a hesitant child as non-verbal. With patience, encouragement, and personal support, he helped that child work up the confidence to board the slide and ride down. “He built a true connection with the child, and wow did that kid have the biggest smile at the end,” says King.

The work doesn’t end at training, though. It’s a continuous project. Crystal’s next focus will be on its food and beverage area, where it plans to provide calming tools, like fidget spinners, and make the setting more comfortable for all. The resort also intends to add more comfort zones in the future. “We don’t want to say, ‘yes, we have a place for you, but it’s a half mile away,’” says King.

Travel can feel overwhelming for families navigating sensory needs, because “it’s too stressful,” King adds. “We want to be the place they are completely comfortable coming to.”

Sundance, Utah, used the MIDA financing program to develop a 63-room accessible inn that will host four-day visits for veterans 36 weeks each year.

Sundance, Utah, used the MIDA financing program to develop a 63-room accessible inn that will host four-day visits for veterans 36 weeks each year.

Sundance: A Veteran-Focused Accessible Inn

What if making a scenic mountain resort more accessible—physically, financially, and emotionally—could also strengthen its business? At Utah’s Sundance Resort, that’s exactly what’s happening.

This past June, the resort broke ground on a new 63-room accessible inn that will serve a veterans program beginning in 2026. For 36 weeks each year, the inn will host veterans and their families or companions for four-day stays, where they’ll share meals, gather in comfortable spaces, and take part in seasonal adaptive outdoor activities.

Why Sundance? Jensen, a partner and investor in the Sundance Mountain Resort ownership group, points to the land itself. “Robert Redford said the first time he drove up that canyon, he said, ‘oh my God.’ I still think that feeling continues. Every time I drive up, I’m reminded how remarkable a setting it is. It’s the unique notion of location and how mountains can heal. You can just feel it here.”

When Broadreach Capital Partners and Cedar Capital Partners purchased Sundance from Redford in 2020, they pledged to honor his legacy—no buildings taller than the trees, a strong focus on the environment—while tackling overdue upgrades. ADA compliance, lift replacements, and eventually, new lodging were all part of the “Sundance 2.0” plan.

The inn project accelerated after the team learned about the Grand Hyatt Deer Valley’s partnership with Utah’s MIDA (Military Installation Development Authority), a novel financing program that allowed Sundance to secure below-market rates. “It made the project viable and allowed us to move ahead sooner,” says Jensen.

In its desire to serve veterans, the resort also had an advantage: Jensen’s wife, Cheryl, who founded the Vail Veterans Program, provided deep insight into how to build a program that truly matters and works.

“Utah is very focused on veterans,” says Jensen. “It feels good to be part of that. I already have employees telling me, ‘I’m so proud we are doing this.’

“Veterans come home and feel forgotten,” he adds. “So, we want this to help them build resilience and confidence and get a break from what they are dealing with.”

The effort delivers on both business and mission, he says. “This helped us take a new position and yet still maintain the character of Sundance that Robert Redford protected for decades.

“It’s a win-win,” Jensen says.

Whistler's improvements include adding a ramp to Steeps Restaurant (left) and Roundhouse Lodge (right).

Whistler's improvements include adding a ramp to Steeps Restaurant (left) and Roundhouse Lodge (right).

Whistler Blackcomb: Accessibility Certification Pilot

Whistler Blackcomb in British Columbia has long been committed to accessibility, thanks to decades of work by Whistler Adaptive Sports and its role as host of the 2010 Paralympics and the 2025 Invictus Games.

About five years ago, though, the resort expanded the scope of its commitment. “Skiing and riding are multi-generational sports in a way most other sports are not,” says business development senior analyst Omer Dagan. “I ask folks how old they will be when they stop skiing and riding, and many say 80, even 90. But [leaving the sport] is a gradual process, and often the barriers have little to do with skiing ability. You can’t hear as well. Stairs, particularly in ski boots, become an impediment. The schlep gets harder. It’s not necessarily the skiing that stops them.”

To address those barriers, Whistler formed an accessibility working group with representatives from every department and input from adaptive athletes. At the group’s recommendation, the resort decided to pursue a Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification (RHFAC). RHFAC is a Canadian program that rates the meaningful accessibility of buildings and sites based on the user experience of individuals with varying disabilities. “They’re the global industry leaders in accessibility assessments for everything from airports to stadiums,” says Dagan. “It became clear to us that they could provide us with a roadmap.”

The resort didn’t expect an easy path. “We were under no illusion that our facility would be rated particularly well,” he says. And this was RHFAC’s first assessment of a four-season resort, so there were some unalterable variables to account for, such as the possibility of rapid snow accumulation against structures in winter.

Following the audit, the resort focused first on the Roundhouse Lodge, a busy hub at the top of the wheelchair-accessible Whistler Village Gondola. The 79 pages of the report dedicated to the Roundhouse flagged everything from outlet height to door pressure. Improvements included a ramp to Steeps Restaurant—once accessible only by stairs or patio—and a new non-slip walking surface in the lobby. The upgrades pleased guests and eased life for staff, especially servers.

“We’re not just stopping here,” says Dagan. Next steps include assistive hearing technology, replacing doorknobs with easy-to-grab handles, and improving access to chair lifts and gondolas for specialized equipment.

The Bigger Picture

Across North America, resorts are embracing accessibility and inclusion efforts that go beyond ADA requirements. Sometimes it’s as simple as moving a trash can or adding a lanyard. Other times it’s major infrastructure or long-term partnerships.

The common thread is intent. It’s a journey to accomplish these aims—and one the industry is increasingly willing to take.