In the post-Big Brother world of modern technology, the big satellite in the sky has its eye on you. Out in earthly orbit, the basis for the all-knowing Global Positioning System (GPS) contains within its powers the ability to track your every move.

That might sound ominous enough to trigger a host of existential anxieties, but let’s accentuate the positive: GPS might be the next big thing to improve the efficiency and overall quality of snow grooming. GPS systems are just beginning to appear in groomer cabs as a tool with a host of potential benefits, including efficient deployment of grooming resources, increased fuel economy, increased labor efficiency, and snow-depth measurement. All thanks to some eye-in-the-sky thingamagig hanging around in the ether, miles from Planet Earth.

The concept of using GPS as a grooming tool is relatively new, and few resorts (at least in the U.S.) are currently using it. But the ski industry has been somewhat slow on the uptake in putting GPS to use. The potential benefits of the technology have been known and applied in a productive way in a variety of industries for at least a decade.

At the consumer level, GPS has been a handy aid in everything from driving directions to determining yardages in golf. But perhaps more instructive for ski-area grooming managers, GPS has become such a widely used tool in the agro-economy that it has spawned a nouveau term, “precision agriculture.” According to GPS.gov, the U.S. government’s official GPS site, precision agriculture involves “prescribing and applying site-specific treatments” (e.g., fertilizers and insect-control strategies) and minimizing redundancy in accurate field navigation for “maximum ground coverage in the shortest amount of time.”

Such strategies should sound familiar to mountain managers everywhere. After all, doing as much as possible as efficiently as possible and identifying the best ways to cope with a wide variety of terrain challenges should be basic bullet points for any grooming operation.

However, according to John Glockhamer, marketing manager for PistenBully, North American resorts are lagging behind their European counterparts in using GPS as a basic grooming tool. To date, PistenBully has been unable to make significant penetration into the U.S. market with its SNOWsat system. In part that is because, while SNOWsat is standard in the company’s 600 model, it remains an optional add-on for the more popular 400 model. Other GPS-system manufacturers, including Prinoth and Destoy, also report less-than-robust demand.

In part, market resistance might be due to the fact that the technology, as applied to snow grooming, is relatively new. Jonathan Thibault, product manager for Prinoth, says that its GPS-based system, Snowhow, was first tried on-snow just five years ago; according to Caleb Hamilton of Destoy, his company’s system is even newer, just two years old. Perhaps ski area operators are waiting for such technology to develop a track record of usefulness and reliability before they jump on board. As Glockhamer puts it, perhaps U.S. ski areas are waiting for “Europe to get up and running and get the bugs out.”

Manufacturers also concede that up-front expense might be a deterrent, although within the overall context of snowmaking and grooming, the costs seem relatively small. According to Hamilton, an initial set-up, involving the establishment of a base station and the fitting of two cabs with GPS units, runs $20,000 to $30,000. Glockhamer says that, for a fleet of 10 cats, the per-cat cost is about $8,000. While that is not insignificant, companies say that through fuel savings and other efficiencies, the systems pay for themselves within one to three years.

GPS SYSTEM BASICS

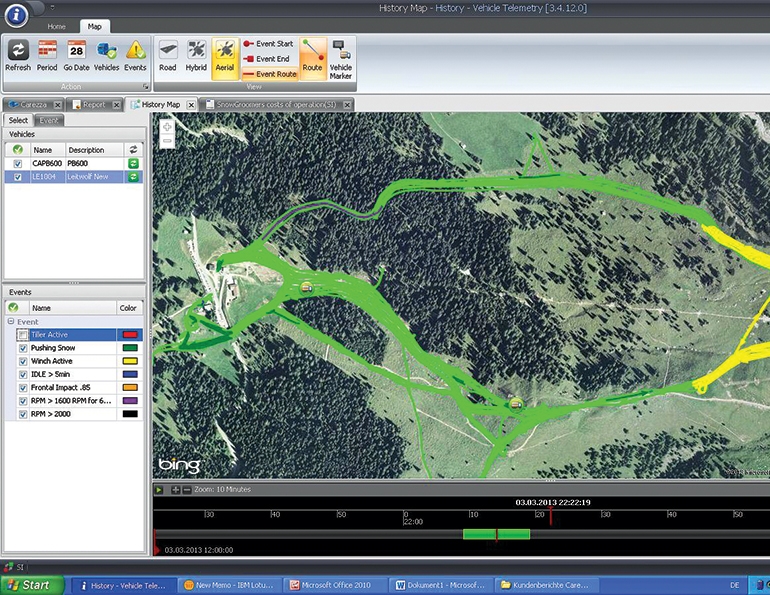

So what exactly are you getting? GPS systems start with at least one base station for data collection, management, and storage. Base stations work in concert with small, mounted units within cats to provide operators with real-time info on precisely where they are, where they are going, what obstacles or problems they might encounter, and what conditions they are dealing with.

For precise snow-depth measurement, a second base station may be necessary to provide what Glockhamer calls “differential GPS.” A single base station, providing locational accuracy within a foot or two, is sufficient in a fleet-management application, but much greater precision is necessary to pinpoint snow-depth variations. Differential GPS employs multiple base stations and can be accurate to 10 cm (about four inches).

Rather than going the differential GPS route, Prinoth supplements its GPS system with radar sensors fixed to the bottom of grooming machines to measure snow depth.

Installation of GPS units is relatively quick, about three or four hours, according to Glockhamer. Some new groomer models come pre-equipped with GPS devices, but any groomer can be retrofitted. While there is obviously a training period, as with any new technology, manufacturers claim that both mountain managers and cat operators move along the learning curve fairly quickly.

GPS BENEFITS

One potential source of efficiency: Using the GPS system, a ski area can map its terrain to identify potential problem areas—e.g., low-snow zones, varying slope pitches, lift towers, snowmaking hydrants, etc.—and devise a precise grooming plan accordingly. Hamilton describes Destoy’s system, based on the Raven Precision system widely used in agriculture, as “a tool for the operator to make his runs more efficiently.” That means providing the operator with guidance that will allow him/her to follow precisely the most effective, productive, and time-saving grooming pattern and to line up overlapping runs properly. This can be especially useful in low-visibility conditions, he adds.

In addition to providing cat operators with a tool to make their runs more efficient, GPS-based systems can also be an effective fleet management tool for the mountain manager. GPS systems have been used extensively in this way in the transportation, mining, and trucking industries, among others. Thibault calls Snowhow “a very powerful management tool” for maximizing fuel efficiency, groomer deployment, grooming patterns, and even groomer engine settings that will ultimately result in “improved piste quality.”

According to Glockhamer, SNOWsat can provide grooming managers with a wide array of data—acres groomed, number of laps, hours, machine idle time, even engine rpm—that can be instrumental in developing a fleet-management plan that optimizes resources. A grooming manager can choose whatever set of data seems most pertinent to any operation and apply it.

For all that, GPS systems don’t automate the decision process. GPS can provide data, but fleet-management decisions remain in the hands of grooming managers. As Glockhamer puts it, “you have to want to embrace the GPS technology and have the discipline to study the data.”

Traditionally, experience rather than technology has been a grooming operation’s most important asset in building an efficient and effective grooming plan. Indeed, it is unlikely that any technology can completely replace the knowledge of an experienced cat operator familiar with every roll and tilt of a mountain’s trail layout. And none of the manufacturers is suggesting that total automation in grooming is anywhere near to being a reality.

VIEW FROM THE FIELD

Nevertheless, with all the detail that a GPS system can provide, “you can send out a rookie groomer and he can nail it,” says Logan Stewart, mountain operations manager for Timberline Lodge. Timberline has been using a Destoy system for more than a year.

Stewart is particularly impressed with the efficiencies that the Destoy system brings to park-building. “The days of monkeying around are over,” he says, meaning no more guesswork in creating such features as proper ramp angles and properly sized and angled landing zones. Stewart estimates that GPS technology allowed Timberline to save about 20 hours of cat time in building its halfpipe by getting all the parameters right in the first pass or two.

The Aspen Skiing Company has been another early adopter. It is currently using GPS in tracking not only grooming operations but also its over-the-road truck fleet and its snowmobile movements. The resort has a total of 164 vehicles with GPS units, of which 16 are groomers, says Jim Ward, director of purchasing.

The groomers are equipped with Isaac Instruments units that are used for tracking historical, rather than real-time data, according to Ward. Aspen is using the data collected to develop more efficient grooming patterns and in particular to reduce fuel usage by reducing idle time. “We’ve been able to reduce our idle time from 17-18 percent to 12-13 percent,” he says. By operating more efficiently, he notes, “we’ve been able to reduce our fleet by two (cats), so in that way the system has paid for itself.”

An historical data system, of course, does not allow cat operators to use real-time feedback while on the mountain. According to Ward, Aspen will be demoing Prinoth’s real-time system this winter. “I am anxious to see what it can do for us,” he says.

Mount Snow is anxious to gain the benefits of GPS, too, but is not yet willing to make the investment. The resort demoed a system last year, and while Dave Moulton, director of mountain operations, was impressed by the capability to “track passes and routes and overlapping patterns,” he still found that the technology is “fairly technical and takes a little bit of work for cat operators to get used to. We had mixed reviews from our operators.”

One operator called GPS “a great tool if they can get it as precise as it needs to be. And you still can’t replace the experience of knowing your terrain, something that can only be learned over time.”

That said, Mount Snow still plans to adopt GPS technology in the future, according to Moulton.

BEST IS YET TO COME

For all the current benefits, even the manufacturers of GPS systems concede that the technology is still a work-in-progress. “It is evolving so fast,” says Thibault of Prinoth. “We’re still bringing in new features. There are some hardware improvements, but it is mostly software.” Because the software for all of the systems is primarily web-based, upgrades can be downloaded automatically.

Hamilton believes that GPS technology will have industry-wide benefits when it comes to park-building by providing data that will create a standardization method for assuring park uniformity and safety. “This is a tool to assure that all the angles and lines are right,” he says.

As GPS guidance capability continues to spread into a broader spectrum of personal and business life, it seems inevitable that, in the not-so-distant future, it will become a standard tool for grooming operations. The eye in the sky is keeping a close watch on what is happening at mountain resorts everywhere.

Browse Our Archives

November 2013

Techno Grooming

- Push to The Latest: No

- Show in The Latest?: No