Our goal, as builders, has always been to minimize risk while providing the best experience for everyone. We’ve learned a lot over the years without much guidance towards what the actual features should look like. Thankfully, there are passionate people who put in long hours building features, communicate with each other, and observe the athletes and guests who use their creations.

These dedicated builders have been getting together for more than a decade at Cutter’s Camp, NSAA regional shows, and independently to discuss their techniques. They are always studying and expanding their education, spying on each other, and absorbing information relevant to their world, despite it not being a formal field of study. Because of this devotion, a group of expert freestyle terrain builders from coast to coast have joined forces to help streamline park features into predictably built, consistently fun, and reasonably safe experiences.

Nevertheless, some misinformed people who don’t care to understand the sport claim that freestyle terrain professionals, under the direction of resort leadership, have been irresponsibly experimenting with the general public. While we all know this is simply not true, it is frequently the argument for standardizing the design and construction of freestyle terrain.

Science and Design

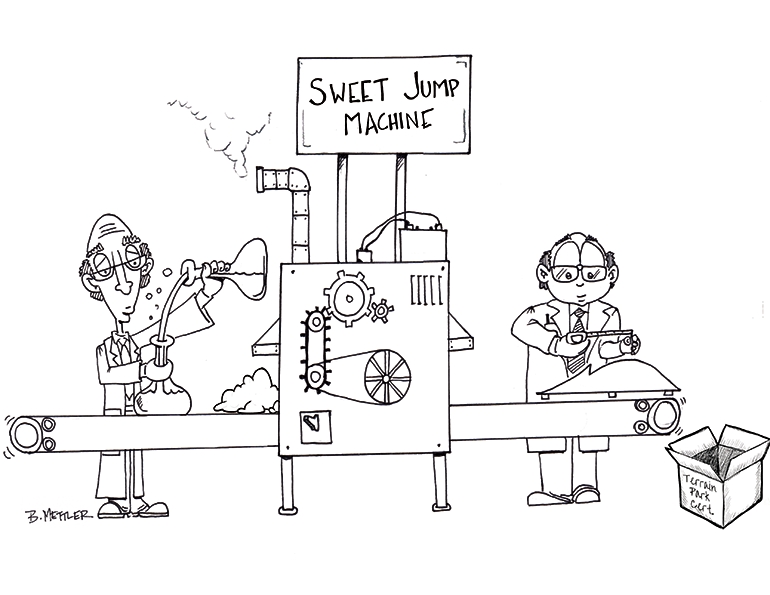

The classically educated-set views jump building as an academic problem and is driving the demand for standardization based on a mathematical solution, without including human factors. Intellectually, this argument seems quite simple: 1) create a model using basic ballistic trajectory physics that allows the greatest margin for error; 2) build a jump to fit this profile, and 3) create a predetermined starting point for each feature in order to control the user. The expectation is that this process allows builders to construct a feature that anyone, on any equipment, at any speed, with any snow condition, can land safely.

The reality is not this simple, and no jump can be designed to be perfectly safe.

The internal side of this argument speaks to the efficiency, quality, and consistency of global freestyle terrain operations. If we try to break down the feature design and construction process into tangible, trainable steps, something that has historically been considered something of an art form could turn into a logical, repeatable process that can be explained to the layperson. Include all of the factors that go into the construction of one feature—demographic information, trail selection, grade studies, snowmaking capacity, resort philosophy, park size, flow, availability of experienced builders, measuring procedures, and so on—then add trajectory physics to the mix to create one golden formula that spits out a shape that any builder can reproduce. Easy, right?

There is an industry-wide appetite for some kind of trainable system for feature construction, paralleled by an expectation of professionalism coming from not just the outsiders, but our guests as well. There exists, quite simply, a demand for knowledge that needs to come from more than just field experience and trial-and-error.

Where this education will come from seems less clear. Independent “experts” and formal groups like U.S. Terrain Park Council have tried to tell the industry what things should look like without understanding the sport. Industry subcontractors like Snow Park Technologies have been successful in elevating the programs at many resorts, but are an added operational expense. NSAA has given us guidance with risk management and best practices, but may not be in the position to dive into the formulas and numbers game.

That is not to say that any one group should be ruling the empire of how to build sweet jumps, but it is inevitable that someone is going to try. As the industry recognizes this, the challenge falls into the hands of those who will ultimately be responsible for developing freestyle terrain in the future.

Formalizing the Process

In 2011, this conversation emerged in ASTM, an independent, non-profit organization that develops voluntary consensus technical standards for a wide range of materials, products, systems, and services. ASTM impacted the ski industry by standardizing how ski boots and bindings work together, and how to set them for release from each other. Because of these standards, equipment has improved and we’ve seen about a 90 percent decrease in lower leg fractures in the sport.

The keys to success of this approach: it must be industry driven and voluntary, and provide a solution to a problem that is clearly evident, from the standpoint of those who understand the industry best. But with freestyle terrain, the problem is not so clear cut—it is challenging to identify whether a specific injury or injury-causing mechanism even exists. Despite the lack of a definable problem, the question has been presented, and exploration into developing a standard or standards has begun. ASTM provides the most objective forum.

Initially, this discussion took place under the “new projects” umbrella, but in July 2015, an official subcommittee was named—F27.70 Freestyle Terrain Jumping Features. F27.70 is focusing only on jumps built for public use (not jibs, halfpipes, or any other park elements).

To develop a big-picture standard for a topic with so many variables, the object must first be broken down into its individual elements. Once these are defined (think a glossary of terms, like “takeoff,” “landing,” “approach”), then one can begin to take measurements and research the role each component plays and how they relate. This requires a method of measurement that can be repeated accurately, with consistent measurements across different mountains with different people conducting the research. After collecting sufficient data that represents a large portfolio of features, the data can be compared and formulas for relationships between parts of the feature can be explored. If a magical standard ratio surfaces in this process, the mystery is solved.

At each stage in this process, a proposal is made to add a piece to the overall standard. For instance, a glossary of terms is out for ballot, and will be debated at the winter meeting of ASTM F27 (Jan. 21 in Reno, Nev.). This first, and arguably simplest, step has taken four years, and that suggests that the timeline for future progress will be hard to predict. Then, consider how much freestyle terrain construction has advanced over the last decade, and one may conclude that by the time it is completed, any standard will likely be based on techniques already in wide use.

How would such a standard come about? It may start with reverse engineering successful jump features, then outlining a method for re-creating those jumps in a variety of conditions. The ultimate goal would be to create a trainable tool that resorts use to streamline jump design and construction, provide consistency without stifling creativity, and allow the broadest range of users the greatest margin for error when jumping.

Checks and Balances

Since this process started in ASTM, many resort representatives have joined F27, including some very talented freestyle terrain builders from across the country. Combined with engineers, risk managers, resort management, and others with a vested interest in the sport, a diverse team is approaching the challenge with appropriate checks and balances. This will allow the process to maintain an objective, constructive, and realistic path to answer some tough questions, understanding that resorts need a standard that can actually be applied by their staff. If the standard is too burdensome or stifles a resort’s ability to provide the service its guests demand, then it is ineffective and defeats the purpose.

Is that possible? We won’t know for some time. But here are two options for what a standard might look like, depending on who writes it:

- A set of design parameters for cookie-cutter jumps that stand alone in individual, gated venues. Each resort offers a handful of jump sizes, and each jump stands alone. These jumps would be built to a predetermined specification, use a designated starting point, and have a shallow trajectory that keeps the jumper as parallel and as close to the surface as possible after leaving the ground.

- A system for creating jumps in terrain parks, taking into account all of the variables in terrain as well as how the guest will interact with the environment. Jumps of all different shapes and sizes exist among other features in the park, but each jump has been crafted with an understanding of how the individual components of the feature relate to one another. The measurements fall within a range that is appropriate for the available speed, diversity of users, and variety of snow conditions, to allow for the greatest margin for error.

The best possible outcome would be to develop a set of tools to assist all programs, large and small, to consistently provide stimulating and reasonably safe jumping features. A well established terrain park system will have the means to rapidly get new builders up to speed, and allow a small resort with limited resources to provide a scaled down, but equally rewarding park experience.

In order for resorts to continue to offer the quality, quantity, and variety of features their guests demand, the process has to be controlled from within. While it may not be all peaches and sunshine along the way, it is also not a dark cloud hanging over freestyle terrain that signals the end of fun as we know it.