The Caldor Fire was three miles away when Sierra-at-Tahoe GM John Rice realized the firefighters amassed in Strawberry, Calif., wouldn’t be able to stop the blaze. Thick smoke filled an eerie orange sky. When the wind gusted, Rice could see the flames moving up the canyon. He remembers picking up blackened oak leaves blown in from miles away and thinking, “It’s coming.” Not for the first time, Rice offered Sierra-at-Tahoe as a staging ground to Cal Fire. This time, they finally said yes.

Caldor is only the second wildfire in history to burn from one side of the Sierra to the other. Over 69 days, it burned 221,835 acres—roughly the size of New York City’s five boroughs—destroying 1,003 structures in the process and prompting the evacuation of more than 50,000 area residents. Despite rigorous mitigation efforts, 80 percent of Sierra-at-Tahoe’s 2,000 acres were impacted in the blaze. A maintenance structure, and the $5 million worth of equipment and gear within, was lost. Six of the ski area’s nine lifts suffered significant damage.

In the 10 days before the fire hit the ski area, Rice was repeatedly assured that the blaze would be brought under control. But control is something of an illusion when facing down a force of nature. Fanned by wind and fueled by dense forests dry from drought, the fire grew at unprecedented rates, covering 10,000 to 40,000 acres a day, all the while barreling closer to Sierra-at-Tahoe. Even as analysts worked around the clock to predict its next move, Caldor continued to outperform firefighters’ efforts to contain it.

“Disasters don’t follow the plan book,” says Rice. “But we did have a plan.”

BRACING FOR IMPACT

After 29 years as general manager of Sierra-at-Tahoe and more than 40 years on the California ski scene, Rice is well acquainted with fire season. As a member of his local fire board in Lake Valley, Calif., he is better versed than most in the realities of the wildfire danger that plagues the West each summer. Not content to watch this fire unfold around him, in the days leading up to Caldor’s arrival on site, Rice drove back and forth daily to Placerville, nearly 50 miles away, to attend incident command meetings as a Lake Valley Fire representative.

It was through these breifings from Cal Fire officials that Rice was able to keep a pulse on the ever-evolving situation. “I was able to get into some conversations behind the scenes and really kind of understand how things work” in regard to Cal Fire’s containment strategy, he says. “It was a real good education for me.” The meetings also kept Rice in contact with those in charge.

Hi, I’m John. When a fire burns for weeks, as Caldor did, there is typically a changing of the guard—old fire crews, with their analysts and commanders, cycle out and fresh teams arrive on the scene, ready to bring new energy, new eyes, and new ideas to the containment effort. In Rice’s experience, though, that transition causes a hiccup in communication. Every few days, he was introducing himself to new leaders, first as John from Lake Valley Fire and then, as Caldor drew closer, as John from Sierra-at-Tahoe.

Hi, I’m John. When a fire burns for weeks, as Caldor did, there is typically a changing of the guard—old fire crews, with their analysts and commanders, cycle out and fresh teams arrive on the scene, ready to bring new energy, new eyes, and new ideas to the containment effort. In Rice’s experience, though, that transition causes a hiccup in communication. Every few days, he was introducing himself to new leaders, first as John from Lake Valley Fire and then, as Caldor drew closer, as John from Sierra-at-Tahoe.

As John from Sierra-at-Tahoe, Rice used his time at incident command meetings to secure the ski area as a staging site for crews beating back the blaze.

Ski areas—with their large water reservoirs, ample defensible space, vast parking lots, and wide-ranging facilities—lend themselves well to such firefighting operations, and the precedent is well established. Showdown, Mont., served as a full-blown fire camp for crews working on the Divide Complex in July 2021. Crews staged at China Peak, Calif., in September 2019 when the ski area was facing a direct threat from the 167,000-acre Creek Fire.

The arrangement is mutually beneficial. Of the manifold advantages of serving as a staging area, the most obvious is having motivated firefighters right on site, ready to defend your property in the containment effort.

Sierra has a standing agreement to stage government contractors and county, state, and federal fire crews in the event of a fire or an emergency. The resort has staged fire crews in the past when the threat was less immediate. Despite all this, it wasn’t until the day before Caldor arrived at the resort that incident command decided to use Sierra to that effect.

Evacuate, now. Once the decision was made, there was a flurry of activity. Over a weekend, Sierra was transformed. With the fire only three-miles away, signage, porta-potties, trucks, water tenders, and 60 dozers were brought in. Two strike teams convened by multiple Tahoe area agencies showed up Saturday, Aug. 28, and were placed on standby. Within hours of their arrival, Rice heard over the radio that the containment lines at Strawberry had failed.

On Sunday, Aug. 29, the blaze jumped to Camp Sacramento, right on the other side of Sierra’s West Bowl. After days of waiting and hoping, the fire had arrived. Instead of making a stand, the entire operation was ordered to evacuate.

“I was like, ‘this can’t be happening,’” Rice recalls. He and his mountain manager Paul Beran, the only Sierra employees who had been allowed to remain on site, briefly considered hiding and staying to defend the ski area, but good sense prevailed. They evacuated.

“When I got to my house, you could hardly see through the smoke,” he says. “There were police driving around saying, ‘evacuate now, get out now!’ It wasn’t like you’ve got 12 hours to pack. It was grab whatever you can and go.”

The Caldor Fire pushed into Sierra that night.

“Could two strike teams have stopped this fire? No,” Rice reasons. “This thing was going to come in here and do what it wanted to do, and there was nothing you could do to stop it.”

FIRE MITIGATION 101

If there is one lesson from this story, it is that fires are unpredictable. Thousands of Sierra’s trees burned, while a little wooden outbuilding filled with waste oil on the property survived. Five sprung structures sustained minimal damage—a bit of shrinkage, says Rice.

The brick maintenance shop, however—where Rice and his team decided to store all the new snowcats, winch cats, snowmobiles, and employees’ tools ahead of the fire—turned into a hotbox. Its two-foot-thick I-beams “were like spaghetti, melted like spaghetti,” says Rice. Conversely, “Everything we had in the parking lots was fine. All the equipment, everything we left out, the older snowcats, all that stuff was fine.”

For all of that unpredictability, though, active mitigation strategies successfully preserved Sierra’s base area buildings—the result of good planning.

The plan. Several years earlier, motivated by rising insurance premiums, Rice had put together an extensive wildland fire mitigation plan outlining the ski area’s resources, buildings, and defensible space. A one sheet version became a tool to quickly acquaint incident commanders with the ski area both in the lead up to and aftermath of the fire. The longer version served as the blueprint for Sierra’s extensive mitigation efforts.

Turning Sierra’s snow guns on its buildings was part of that plan. Defensible space work—the creation of a buffer between structures and surrounding fuels like trees, shrubs, and even tall grass—was also provisioned for in the plan.

Hot shots and diaper gel. To support the plan, in the week before the fire’s arrival, well before Sierra became a Cal Fire staging site, the ski area’s insurer MountainGuard sent Sierra an experienced hot shot crew from AIG. The crew sprayed Sierra’s buildings in Thermo-Gel, a fire-retardant polymer slurry modeled after the absorbent gel found in diapers. It’s expensive but effective: “It’s like $500 a gallon or something,” says Rice, “but everything that was sprayed with Thermo-Gel survived.”

A hot shot crew from AIG sprayed Sierra’s base buildings with a fire retardent spray called Thermo-Gel, saving the structures.

A hot shot crew from AIG sprayed Sierra’s base buildings with a fire retardent spray called Thermo-Gel, saving the structures.

“Every resort probably has an annual walkthrough with their local fire jurisdiction and they look at their buildings and check their extinguishers, but going a step further” with the AIG crew was a tremendous learning experience, says Rice.

The hot shot crew showed Rice and Beran how to anticipate where the fire might go by observing where ash and leaves collected in the nooks and crannies of a structure. “We paid special attention to those areas where stuff collects under buildings and around the corner,” explains Rice. The crew also duct taped every single vent on every single building to prevent any sparks from sneaking inside.

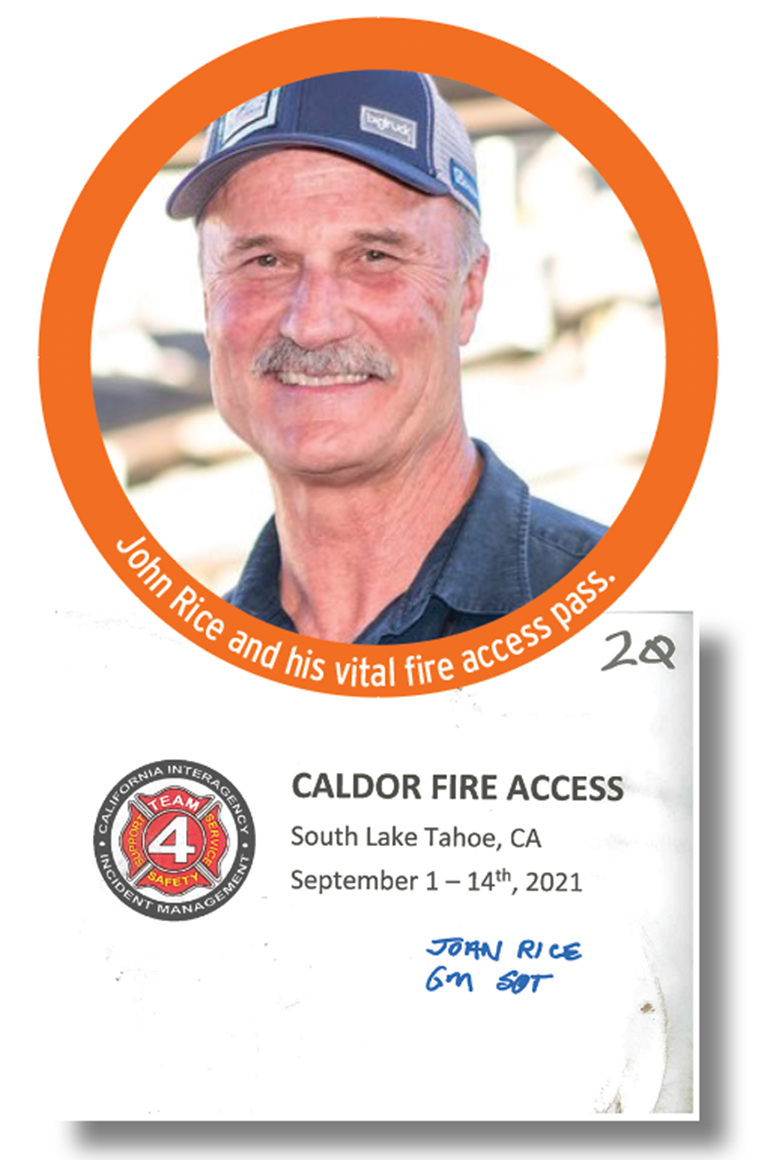

Relationships are everything. With a massive conflagration baring down on the ski area, access to the site for this mitigation work was not a guarantee. “The road had been closed about four days prior,” says Rice. “No one could get here.” Rice used his fire pass and his relationships with fire patrol to get past the blockades.

Those relationships would prove critical in returning to Sierra after the fire had passed through as well. “The relationships that we’d built for years with law enforcement were key because they’re standing at all these road closures, and if you don’t know the guy, it doesn’t matter who you are, you’re not getting through. They didn’t care that you ran a ski area. If you didn’t have a pass you weren’t getting through,” says Rice.

With an active fire raging in the area, knowing someone on the fire patrol with the ability to authorize access was essential, he explains.

While the fire crews frequently changed over, Rice says the same local law enforcement, fire officials, and forest service officials that he’d long worked with played an integral role throughout the containment effort. “I can’t say enough about how just building trust with those folks ahead of any kind of emergency is going to be beneficial,” says Rice.

Returning to the Resort

Rice was eager to get back to Sierra and assess the damage. At first it seemed like the ski area might have escaped largely unscathed. The base buildings hadn’t burned. The lift terminals and towers all still stood. That was the image and the message communicated by the media—Sierra Survived. Only one building lost. As news coverage followed the fire over Echo Summit to Kirkwood and Heavenly, though, the true scope of the damage slowly became clear to Rice and his team.

Rice recalls driving around to assess the ski area as trees—large widow makers, some 200 feet tall—fell in front and behind him. Flames would burst from broken tree trunks, lighting up the dead red firs like roman candles. Large stands of Sierra’s old growth forests were left yellowed and grey. That’s when it hit Rice: “Oh my God, we’ve got a bigger problem.”

Hazard trees. Sierra brought in the Forest Service BAER (Burned Area Emergency Response) Team and some arborists to evaluate the hazard trees. While the assessment is ongoing, Rice says 80 percent of the ski area’s footprint was affected by the fire. That means thousands of fire-weakened trees that will need to be assessed, felled, and/or cleared in the coming months, forever changing the landscape of the resort.

Eighty percent of the forest at Sierra-at-Tahoe was affected by the fire, so thousands of charred trees will need to be assessed, felled, or cleared.

Eighty percent of the forest at Sierra-at-Tahoe was affected by the fire, so thousands of charred trees will need to be assessed, felled, or cleared.

A tree, hollowed by fire, gives an up-close look at the effects of the blaze

A tree, hollowed by fire, gives an up-close look at the effects of the blaze

Recovery efforts were further complicated after cell service went out (and stayed out) a few days before the fire. The power went out, too. Sierra’s main power source terminated in the maintenance building with the melted I-beams—it literally went up in flames.

To help get Sierra up and running, Rice offered the ski area’s parking lots as a staging site for California power provider PG&E. “They brought in not only tons of equipment, helicopters, and masticators, but also all the stuff to fix the power lines all the way down in the canyon to Grizzly Flats, where [the fire] started.”

Sierra charged PG&E a small fee, and in return PG&E also brought in generators, food, and 24-hour security, which helped keep out the “lookie-loos,” says Rice. “It was a big burden off of our shoulders,” not just because it kept the gawkers away. With trees falling and fires still burning, Sierra was full of hazards.

The ski area was operating on generators until November, a logistical nightmare. “We had to fuel the generators, and to get fuel to a generator you have to drive through an active fire with trees falling,” says Rice. “I mean, these are things you don’t even think about.”

Lift damage. In the weeks after the fire, it also became clear that Sierra’s lifts had suffered significant damage. “We got some folks from lift companies and engineers and state lift inspectors to come in and poke around, and then we started to realize the damage to the lift infrastructure,” explains Rice.

“The communication cables were gone, and you could see where the wire rope had been compromised, where the polypropylene core on some of the ropes had actually oozed out of the rope,” says Rice. Because the fire burned so high and hot in the tree canopy, five of Sierra’s chairlifts sustained haul rope damage. A surface lift was also completely torched. And in the first few days, one of the ski area’s main lifts took five hits as trees repeatedly dropped on its haul rope, derailing it.

A crew assesses the damage to a derailed double

A crew assesses the damage to a derailed double

Industry support. As word reached other operators of the lift damage, Rice says he received an outpouring of support from his neighbors. Mammoth Mountain loaned Sierra a haul rope and some lift towers, and Boreal sent extra comm lines. Palisades Tahoe sent a crew of 16 to work on repairs. Calls came from as far away as Crystal Mountain, Mich., and Jiminy Peak, Mass. The list goes on.

After the fire, Sierra-at-Tahoe’s neighbors rallied to help with the ski area’s recovery.

After the fire, Sierra-at-Tahoe’s neighbors rallied to help with the ski area’s recovery.

Palisades Tahoe sent over a crew of 16 to assist Sierra with lift repairs and other maintenance.

Palisades Tahoe sent over a crew of 16 to assist Sierra with lift repairs and other maintenance.

“That level of support,” says Rice, “I can’t say enough about the beauty of what our industry is and the people. When somebody’s down, everybody’s there to help.”

And it wasn’t limited to mountain maintenance. Boreal, Palisades Tahoe, and Vail Resorts also offered up their areas to Sierra’s competition teams for training. Vail Resorts extended discounted passes to current Sierra employees and their families and plans to honor Sierra’s complimentary “Straight A” passes for local students.

Rice’s former Booth Creek colleague Jessica VanPernis Weaver, who now runs an Oregon-based marketing firm, volunteered crisis communication help, managing the messaging and media inquiries, writing press releases, and more. “That kind of stuff was powerful,” says Rice of Weaver’s help. “And it cost me a hat—she got a flat-brim hat out of it.”

PASSHOLDERS AND STAFF

Communications have been particularly important with Sierra passholders anxious for news on the 2021-22 season. “A lot of people were pressing us for information,” explains Rice. “Everyone needs to know right now. Season pass holders were wondering right now, what should I do? Should I buy a different pass? What’s the deal? And frankly, we didn’t quite understand what had happened,” says Rice, particularly in the early days.

Transparent approach. “When we realized the extent of the damage, we had nothing to hide,” says Rice. Still, misinformation spreads easily, especially on social channels, be it from guests, employees, or the media. And frankly, it’s hard to appreciate just how enormous the scope of the recovery effort is from the outside. With so many unknowns remaining—they were still clearing trees to safely access and assess the West Bowl lifts in November—Sierra had yet to determine when/if it might be open this winter.

Rice is proud of the solution they came up with for passholders: All passes will be valid for this partial season and next season as well. Passholders who are writing off winter 2021-22 can seek a full refund or hold onto their current pass for 2022-23 and receive a $50 rebate, which can be donated back to an employee fund. “More than 50 percent of the people are keeping their pass,” says Rice, and more than 50 percent of those getting the $50 rebate are donating it to the fund.

Rice has seen the same loyalty from employees. With operations reduced as they are—it’s more construction site than ski area right now, says Rice—many of Sierra’s longtime employees had to be let go. He says they worked to do right by staff, providing severance pay and support, including help finding other jobs. Employees took the news with understanding and promises to come back once Sierra was up and running. “That was the hardest thing for me,” says Rice.

RISING FROM THE ASHES

A disaster such as this takes a steep toll on the landscape and the community. “We’ve had dozers here that are taking hazard trees away from the lifts, and so the landscape is changing daily,” says Rice. “When you come in, it’s not what it used to look like.”

Eventually, you get past the grief of what’s been lost, “and it’s like you start believing in what [Sierra] can be,” he says. “Then you forget, you know? I’ve been driving up here for 20-plus years, and you come around the corner and you’re just driving into work and you’re not thinking about it, and all of a sudden you see it and you just go, ‘Oh my God, it happened. It really happened.’”

Sierra faces a multimillion-dollar rebuild, and that’s just the trails and tree work, says Rice. The ski area is working with the county and state to conduct an economic impact report, which will help Rice as he seeks support from various agencies for the extensive remediation work.

What it can be. As he contemplates the task ahead, Rice says he is most excited by the energy and creativity his team is bringing to the table. With so many trees gone, and so many more still to be removed, they face the daunting but thrilling task of reimagining Sierra’s future. “It’s a change in mindset from what it was to what it can be,” says Rice.

Sierra, which operates in the El Dorado National Forest, won’t necessarily be reforested. The West Bowl, once dense with trees, may become a real bowl. And the possibilities for new runs, wider runs, safer intersections, even new snowmaking ponds, are nearly endless. As one Sierra fan wrote to the resort, when all is said and done, “It just might ski better.”

“The landscape’s different,” says Rice, “but it’s still an awesome place to be. So, the challenge now is to see through the obstacles and instead see the other side of possible.

“That’s what’s keeping my flame lit right now.”