In the wake of the Caldor Fire, which scorched upward of 80 percent of Sierra-at-Tahoe’s 2,000 acres in late August 2021, general manager John Rice has been rebuilding the resort and navigating the nuances of Sierra’s insurance coverage. He has found there is no fast track to resolution for a major property claim. And while Rice’s experience is situational, it may be a precursor of things to come for resorts generally. Insurers concede that the market is becoming more complicated—risk is higher (especially in fire-prone areas), claim payouts are increasing, and the premium pool is shrinking.

For ski area operators, the combination of risks and payouts means higher insurance premiums. According to the “2020-21 NSAA Economic Analysis of United States Ski Areas,” insurance expenses for responding ski areas were up 54 percent year-over-year, representing two percent of total revenue.

So insurance has become a thorny topic. We sat down with insurers, experts, and operators to explore the overall insurance market and its impacts on resorts. We also dove into the claims process, and the experiences of operators who are currently going through it, to help prepare others for the ordeal.

Hardest Market in 40 Years

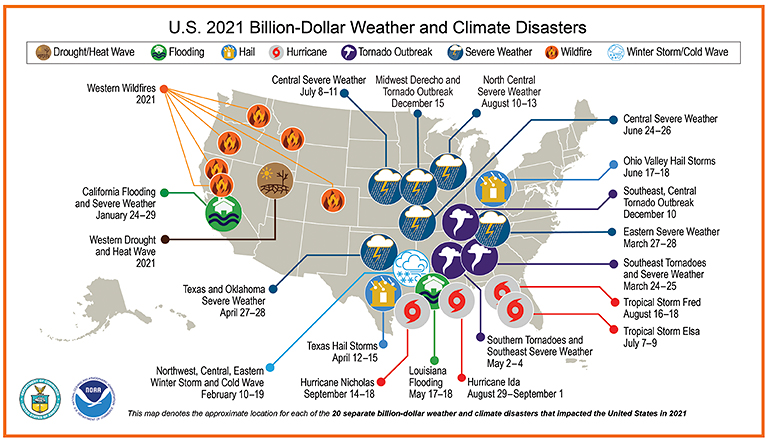

Increasingly severe wildfires and other weather events are contributing to “the hardest insurance market in 40 years,” as MountainGuard senior vice president Tim Hendrickson puts it. (A hard market is one in which it is hard for insurers to find the cash needed to meet their payout needs, and hard for customers to stomach the resulting rise in insurance rates.) Liability coverage factors into the equation, too; juries are awarding increasingly large sums in liability verdicts.

Wildfires are not a new phenomenon. But earlier snowmelt—April snowpack in the western U.S. has declined 19 percent from 1955 to 2020, according to the EPA—a longer fire season, and more fuel availability driven by hotter, drier weather are increasing wildfire risk. EPA data suggest wildfire size and severity have increased in the last 15 years, too.

Wildfires and other weather-related mass property damage have led to huge payouts, and that has helped push up premiums. “The market is not being driven by a single pipe rupture that flooded a house; it’s being driven by unique events like the Southwest freeze in 2021 that cost $155 billion in losses because everybody’s pipes broke,” says Hendrickson. “When you have a wildfire in December in Boulder, it scares the hell out of anybody that’s financially backing people,” he adds, “because they’re only getting so much capital to back the risk. And the capital that they’re getting is not enough to pay for the losses, because the losses continue to escalate every year.”

Increased risk. “It goes back to risk/reward,” explains Safehold Special Risk program director Ryan Patrick. “Somebody’s taking on a bigger risk.”

Mitigating Risk

Insurance companies have always exercised a measure of discretion in taking on clients—the less risky a proposition a ski area is, the better it is for the insurer. So, when it comes to fire coverage, both Hendrickson and Patrick strongly recommend that operators create a wildfire risk mitigation plan. Rice has one for Sierra, which helped the resort prepare as Caldor approached, and would have been even more valuable if authorities leveraged it sooner (See “Fire on the Mountain,” SAM January 2022).

Patrick is starting to see operators submit comprehensive documents outlining planned multi-year investments in fire risk mitigation. One he reviewed recently included “a summary of wildfire risk, forest habitat type and other natural resource considerations, forest thinning and fuels management recommendations, defensible space guidelines, and plans for fuel breaks, obtaining funds for future fire mitigation projects, and monitoring fire danger,” he notes.

A plan is a useful education tool for insurance agents to bring to the carriers and their underwriters when securing coverage. But its greatest potential is in its fulfillment. “If people aren’t willing to take the time and dedicate the resources to do this stuff, the market is going to get even harder,” says Patrick.

Mitigating fire risk isn’t easy or cheap, though. “Capital expense is definitely a challenge, as well as bandwidth,” says National Ski Areas Association (NSAA) director of public policy Geraldine Link. Treating hazardous fuels, for example, is not only expensive, but also requires planning and Forest Service approvals, she says. Forming an evacuation plan is another collaborative undertaking involving local, state, and federal agencies. It is all, nonetheless, necessary mitigation work.

The Claims Process

The promise of property insurance is that it will make you whole in the aftermath of damage, even the catastrophic kind. You have paid your premium dollars, and when circumstances force you to make a claim, money from the premium pool is returned to you to cover your losses.

If the equation is simple, though, the process of being “made whole”—even the definition of that phrase—is not.

Protracted process. “A big claim can take two years to finalize,” says Scott Brandi, president of Ski Areas of New York and a former AIG ski insurance program underwriter. “You are bringing in all of these moving parts, and nothing moves quickly.”

“You feel extremely vulnerable,” says SNOW Partners CEO Joe Hession, whose indoor ski area Big SNOW American Dream was still closed as of mid-February from a small fire that occurred at the facility in late September 2021.

Remediation work after a small September 2021 fire has kept Big SNOW American Dream, N.J., closed as owner Joe Hession navigates the claims process.

Remediation work after a small September 2021 fire has kept Big SNOW American Dream, N.J., closed as owner Joe Hession navigates the claims process.

In the wake of such an event, says Hession, “the first thing that happens is you lose control.” Insurers and regulatory bodies come in to investigate the claim. An adjuster must inspect the damage and determine the insurance company’s payout. Appraisers or specialists may be brought in to valuate structures and other insured items. Remediation work needs to be outsourced.

Plus, there are many different parts of a claim, says Brandi: buildings, contents, loss of income, extra expense, “and then you get into a laundry list of other coverages.”

Within this context, determining the how and the how much of being “made whole” gets complicated. The elements of your policy determine what type of loss is covered, whether you have any sub limits, and at what value your property is insured. For example, in Sierra-at-Tahoe’s policy, anything more than 15 years old is covered at actual cost value, not replacement value. “Most lifts,” Rice notes, “are more than 15 years old.”

A fire-damaged chairlift at Sierra-at-Tahoe.

A fire-damaged chairlift at Sierra-at-Tahoe.

There are also the aspects of a claim negotiated throughout or at the end of the process, such as business interruption. “Loss of income, that’s the last part of a claim that gets resolved, because that’s a financial negotiation,” explains Brandi. Extra expenses, too, are a moving target as far as reimbursement goes.

While navigating a claim is complex and, at times, cumbersome, Rice and Hession have both learned lessons that make for smoother sailing.

Lessons from the Trenches

Know your policy now, not after a loss. “Go through it with your broker and maybe even a third party, every detail,” recommends Rice. “Or at least your risk manager should, so you know exactly where your coverage is and isn’t.”

In that same spirit of preparedness, Hendrickson recommends photo documenting your buildings, inside and out. A photolog provides not only a reference for building materials, layout, and contents, but also proof of loss in the event of a claim.

Actual cost vs. replacement cost. After the fire, Rice wished he had a more comprehensive list of the ski area’s assets and their values. “We had to negotiate almost down to the piece of equipment in the boneyard what the value was, and not having a good inventory was a mistake for us,” he says. “When it comes to hard assets like snow blowers, snowcats—know your equipment, know what your coverage is, and make sure you’re thoughtful about replacement cost versus actual cost.”

Another complication: adjusters likely don’t know the ski industry, or the vendors, says Rice. “For example, we lost six snowcats. There were a couple of brand-new winch cats that are, you know, $500,000 each, which [the adjusters] wanted us to replace with one they found in Montana that had 9,000 hours.” (The issue was ultimately resolved amicably.)

Also, assets are often undervalued and therefore underinsured. “There’s no way you can rebuild a building in today’s market for what it cost eight years ago, especially in the ski industry,” says Hendrickson. “So generally, we find that when we have a large loss, the asset values are undervalued just because of how market conditions have changed.”

Operators can stay ahead of that gap in cost and coverage by regularly updating their asset valuations, and not falling into the trap of accidentally underinsuring items. People are optimistic, so they insure at actual cost value, often at a lower premium, or fail to update valuations having figured they’ll never have to make a claim.

Third-party advisers. When a bad day does come, Hession and Rice both recommend that operators apply careful accounting to any business interruption claims. “I had a business interruption claim years ago at Sierra Summit,” says Rice, “and I learned the hard way that the documentation can make or break whether you get reimbursed on different things.”

Hession suggests hiring a forensic accountant “who speaks the insurer’s language” to help with business interruption claims.

“The second the loss happens, set up almost a secondary accounting system,” Rice adds. Expenses must be properly attributed. “You can’t just lump everything to the fire,” Rice explains, having made that very mistake in the initial weeks after the Caldor Fire. “Have codes, put things in buckets, because ultimately, you’ll have to negotiate with adjusters,” says Rice. Accurate record keeping makes it easier to present your case.

For the aspects of your claim that require negotiation—business interruption, extra expenses, valuations, etc.—Hession highly recommends working with an independent representative, a third-party agent. He’s found his independent rep to be an indispensable interpreter and intermediary during the claims process. Rice echoes that advice.

Both operators also hired coverage counsel. “The coverage counsel, by virtue of being involved at all, instantly changed the conversation” with the insurance company, says Hession. An insurance policy is a legal contract, which makes legal counsel a worthwhile investment in navigating a complex claim.

Take charge. While there is a lengthy process of appraisal and approval for securing advances and reimbursements from the insurer to cover losses, operators can take steps to speed it up.

Hendrickson advises that any insured feeling stuck in limbo waiting to hear from the insurance company or waiting on approval to start work should “pick up the phone and say, ‘Here’s what I want to do. Can I?’”

Hession seconds that idea. “From the beginning, we should have controlled our destiny. We trusted the process, and it was probably the biggest mistake we made,” he says. For example, it took the adjuster three months to find someone to repair Big SNOW’s specialized sprinkler system, and the bid came in at $4 million. Hession’s team found a contractor that could start the work sooner and do it for $1.2 million.

Hendrickson favors the proactive approach. “We want the insureds to get their local contractors to get bids as they would do in any contract construction project,” he explains. “The best [bid] gets forwarded on to our claims people, and they’re pretty quick to say ‘great.’”

“Keep moving, and let us get you some money,” he suggests.

An Industrywide Fight

The insurance market for resort operators is likely to remain hard. As Patrick points out, the insurance industry can only sustain so many large payouts because the pool of premium money is a finite resource. If a major incident drains it, “the insurance industry can’t operate at a deficit for too long, otherwise insurance companies are out of business,” he says.

And the number of contributors to the winter resort pool is shrinking. Vail Resorts has long been “self-insured”, i.e., it insures significant risk within the company. So, its 37 North American ski areas do not contribute to the ski program premium pool (nor do they add to the risk). Other ownership groups are looking to self-insurance as well, at least on the liability front, which is a looming challenge to the traditional insurance model.

“Insurance is about spreading risk,” says Hendrickson. “The smaller the pool, the harder it is to spread the risk.” Additionally, the smaller the pool and the higher the risk, the less capacity there is available to cover certain types of risk.

To be clear, “each ski resort is valued on its own losses, risk management, and risk portfolio,” says Hendrickson. However, “a loss at one ski area may have impacts on other ski areas if they have similar risks,” he explains. And then there’s that globally hardening market.

In the short term, this likely means higher premiums or capped limits for certain coverages. In the long term, there is work happening on multiple fronts.

“These are huge challenges for resorts, with no quick fixes,” says Link, reflecting on rising insurance premiums, “but we are doing the groundwork to address them.”

The long view. As Link sees it, “insurance issues are largely climate change issues. Solving climate change would be a great start in addressing major losses from extreme weather events, and NSAA is fully engaged on climate advocacy.”

To support ski areas in wildfire mitigation, NSAA is also working to provide resorts with education and planning resources, and working with USFS to ensure it prioritizes ski areas for agency investments in fire prevention and restoration. “In the context of our partnership with the Forest Service, NSAA is advocating for a shared responsibility approach with respect to fire prevention and restoration,” says Link.

Fire isn’t the only climate-related issue, though. Hurricane-strength gusts sparked fires and sent up walls of dust from New Mexico to Michigan this fall, and tornadoes ravaged nine states from the South to the Midwest in December. Torrential rain triggered an avalanche that severely damaged a base lodge at Belleayre Mountain, N.Y., on Christmas Day in 2020. The list goes on, and as these events mushroom, more ski areas will inevitably be caught in their path, making this a collective burden to shoulder.

The insurance industry is also turning the lens on itself. “We’re trying to get creative in our world, too,” says Patrick. One possibility is for multiple carriers to contribute to one pool. It wouldn’t drop rising premiums, necessarily, but it might make high-risk coverage viable by spreading it across insurers. “If there’s more people in there taking on that risk, then there’s some staying power there,” says Patrick.

“It is an industrywide fight,” he adds. “We all need to fight together.”