Believe it or not, some version of the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA) Your Responsibility Code has been around for nearly 60 years. It was once ubiquitous throughout skidom, but seems to have become less prominent in recent decades, coinciding with a rise in complaints about a lack of on-hill etiquette. NSAA recently unveiled an update to the code, which should serve as an opportunity to bring the code—and promotion of safe on-hill behavior generally—back to the forefront as a pillar of snowsports culture.

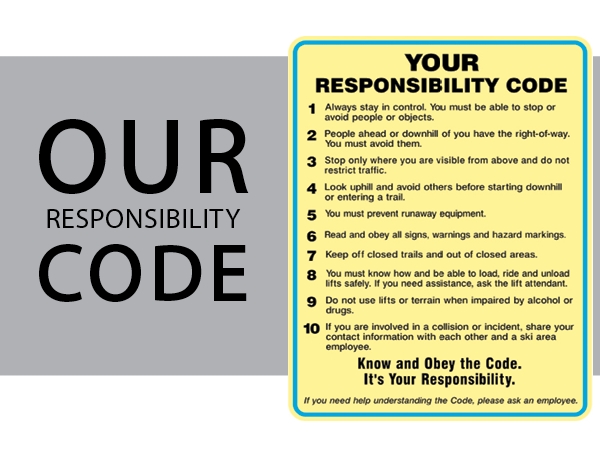

The new code includes two new tenets and revised, more forceful language for the pre-existing seven. It’s the first such update since 1994.

According to NSAA, the update was needed for a variety of reasons: changes in technology and equipment, societal changes in how people view safety and consume messaging, growth in visitation, growing use of alternative sliding devices (i.e., snow bikes), and most urgently, a rise in on-hill skier collisions and hit and runs.

That last item is related to the first. Among the changes in equipment since 1994, the stability of snowboards and wide skis allows downhillers to go faster than in the past. Unfortunately, their awareness level doesn’t always rise along with the speeds they are traveling, and that can lead to collisions.

Many observers, including yours truly, have noticed an increase in reckless behavior and poor on-hill etiquette in recent years. Knowing the code and using it as the guide for how to conduct oneself while skiing/riding is not as prevalent as it once was, and it shows. It’s worth the energy to adjust how we communicate the code, and to ensure all staffers know and model the behaviors it sets forth.

A WORTHWHILE PROCESS

The new Your Responsibility Code (YRC) was unveiled in the fall of 2022 after a thorough, 18-month process. This included gathering feedback from various stakeholders and convening a working group of risk management, legal, and human factors experts that obsessed over the minutiae of the language to be used.

Strong language. The working group aimed to make the language as concise as possible while balancing both its legal and behavior-influencing value. “The primary purpose of [YRC] is to warn and inform people, and influence their decision-making and conduct when they’re participating in the sport,” says Mark Petrozzi of AlpenRisk Safety Advisors, who was on the working group and chairs NSAA’s risk management committee.

On the legal side, for example, YRC is pervasive enough that it’s difficult for a plaintiff’s attorney to argue that an incident occurred as a result of a ski area’s failure to warn and inform. At minimum, the is Code posted on ski area websites and on-property collateral.

To make the tenets more influential and adapt to how people consume information and respond to direction nowadays, the code is now “written as imperatives,” says Petrozzi. In other words, the tenets are written as unambiguous commands.

For example, “Observe all posted signs and warnings” was changed to the more direct “Read and obey all signs, warnings, and hazard markings.”

“Think of it from the standpoint of influencing people’s behavior,” says Petrozzi. “If we say ‘observe’ a sign, that’s different than telling somebody—in 2022 and beyond—to ‘read and obey.’”

Notably, the working group included human factors experts. Human factors is a science that integrates human characteristics, capabilities, and behavior into designing products, systems, and industry-wide safety rules. These experts provided insights about word use (would today’s skier/rider understand the phrase “right of way” in the context of participating in skiing/riding, or “yield”?), sentence length, and even things like using all caps or mixed case, bold or not, etc. cont. »

Two new commandments. In addition to changes in the language and presentation, two new tenets were added:

Do not use lifts and terrain when impaired by alcohol or drugs.

If you are involved in a collision or incident, share your contact information with each other and a ski area employee.

Also, the two sentences of the sixth provision in the previous version of YRC (Observe all signs and warnings. Keep off closed trails and out of closed areas.) are now separate provisions, with the aforementioned change from “observe” to “read and obey” made to the former.

Continental consistency. With these revisions, Your Responsibility Code in the U.S. is effectively the same as the Alpine Responsibility Code used in Canada. Moving forward, the signage and digital assets for both codes will utilize the same colors and design elements, to maintain consistency on both sides of the border.

While the YRC isn’t in any particular order of importance, the NSAA working group kept what is arguably the most important tenet as number one: “Always stay in control. You must be able to stop or avoid other people or objects.”

SET A GOOD EXAMPLE

“Knowing—and modeling—the Code should be in your ski area’s DNA; from patrollers to instructors to your marketing team, everyone can play a role in getting the Code in front of guests,” says NSAA director of marketing and communications Adrienne Saia Isaac.

The “Your” in Your Responsibility Code addresses the participant, regardless if the participant is a guest or a ski area staffer. That said, at the bottom of the new YRC signage, it says: “If you need help understanding the Code, please ask an employee.”

Call to action. Whether the working group intended for this to be a call to action or not, that’s how I see it. By directing readers of YRC to ask an employee for guidance if needed, it’s telling ski areas that if they don’t already train all staff to know and model the code, start now.

Of course, not all employees embrace the code, especially tenet #1. In keeping with the new, more direct language of the code: breaking tenet #1 must stop.

That said, a lot of ski areas already do an excellent job of communicating and modeling good on-hill behavior. These ski areas take equal responsibility in building a culture of safety and respect by acting both as good stewards of YRC and adherents. They treat it like it’s “Our Responsibility Code.” (For specific examples, see “Safety First” on p. 50.)

“You have to lead by example, which is something we should be doing as someone wearing a uniform and representing a mountain,” says Ali Spaulding, daily lesson supervisor at Sugarloaf, Maine, and a PSIA-East examiner. “That means stopping in the right place, being respectful, passing in a safe manner, giving people plenty of space, merging carefully.

“When you’re on the hill, you don’t necessarily have to say it in order to teach it, you just have to practice it,” Spaulding says—at all times, in or out of uniform.

MORE RESPONSIBILITY

We can all agree that if every participant put the tenets of the code into practice, everyone would enjoy a safer ski and ride experience. That might not be realistic, of course. But it should be the goal.

As Spaulding points out, many guests thrive on disobeying signs and safety messaging. “Some people pay attention to it, and others take it as a challenge,” she says, by going fast in slow areas and slaloming through ski school groups.

Other guests simply pay no attention to the code. “I think the responsibility code is ignored by way too many skiers,” says Neville Sachs, a longtime ski industry engineer and volunteer ski patroller in upstate, N.Y. That reinforces the need to ramp up awareness.

As a patroller and a guest, Sachs has seen an increase in collisions that were the result of one person “not having good perspective of what’s going on around them,” including hit-and-runs where the offenders didn’t stop to offer help. “I know we can’t teach morality, but an increase in the emphasis for personal responsibility would help the entire world,” he says.

Avoidable incidents are the scariest byproduct of participants not following the rules. I know this first hand. In January 2021, my then-six-year-old daughter got taken out right in front of me by a 20-something snowboarder on a wide-open beginner trail with few other people on it. We were less than 200 feet from the bottom, and she was skiing about 20 feet in front of me. He came in from my left and smashed into her.

Thankfully, the only thing that broke in the incident was one of her ski bindings. I wanted to break the guy’s face, but I settled for an f-bomb-laden tirade instead. He apologized and, with no injuries, we parted ways.

That collision could’ve been much worse, and was very avoidable if some basic points of on-hill safety were followed: the guy was riding too fast on a slow skiing trail; he was out of control; and he came in from behind us, not giving the downhill skiers the right of way.

REINVIGORATION TIME

Yes, I am now hyper-sensitive to others’ on-mountain behavior. And I’m an advocate for ski areas to go above and beyond to educate, model, and enforce the tenets of Your Responsibility Code.

Ski area operators must embrace the opportunity that the revised YRC provides. As the full rollout happens over the next couple of years, use that to introduce new approaches to educate staff on the value of following the rules, and promote the code to guests in creative ways.

If stagnation fostered complacency, the revised language and look of our industry’s most sensible safety campaign should reinvigorate your efforts to ensure everyone sees it the same: Your Responsibility Code is also My Responsibility Code—which makes it Our Responsibility Code.