Think “ski areas” and you think winter, snow, lifts, and après, right?

Not so fast.

In the past decade, ski areas have emerged as notable players in the destination travel summer market, and in every month outside of the winter season, too. In this renaissance, of sorts, for the mountain destination travel industry, resorts are evolving from snowsport-centric winter playgrounds to sophisticated, year-round destinations in a way that’s broadening their guest demographics, changing how their committed winter visitors view their product, and turning three or four months of conditional revenue into filling the till almost year round.

To most of you, this isn’t news. In all but the most established mountain destinations, the growth of the summer and shoulder seasons has been meteoric since 2009.

To most of you, this isn’t news. In all but the most established mountain destinations, the growth of the summer and shoulder seasons has been meteoric since 2009.

But the forces involved are not so clear-cut as revenue growth, and as the proverb tells us, not all that glitters is gold.

In this three-part series, I’m going to look at some of the benefits and challenges presented by the growth of the non-winter season in traditional ski destination communities, hopefully seeding a few other discussions in the industry.

But first, some background.

Recession Economics

Back in 2008, as the Great Recession was gearing up, the summer season was an also-ran in many, but not all, ski destination communities. With some notable exceptions near mountain lakes and National Parks, ski destinations seemed, for the most part, content with the high revenue generated over the ski season—around mid-December to mid-April, depending on conditions. It was defined by very high demand holidays and a steady pattern of weekend/weekday visitation that made life relatively predictable, though beholden to snow.

With the collapse of Bear Stearns in September 2008, the bottom began to fall out of the consumer market, and all segments of the ski industry cut rates dramatically in an ultimately fruitless effort to retain revenue gains. In the end, the greatest legacy of the 2008-09 rate cuts was the inability of the industry to recover quickly, with rate parity to pre-recession levels not being achieved until 2014. The resulting long-term revenue declines put some resorts on the defensive, as others moved to offense.

Oktoberfest at Snowbird, Utah, goes on for several weekends in summer and fall, drawing thousands of overnight visitors and boosting non-winter revenue.

Oktoberfest at Snowbird, Utah, goes on for several weekends in summer and fall, drawing thousands of overnight visitors and boosting non-winter revenue.

While the recession was picking up pace, operators were becoming increasingly aware of another existential threat to the future of the industry: climate change. They started thinking about how to apply Darwinism to their business case: evolution or extinction.

So, under negative threat from the wild cards of economy and climate, attention was turned to the eight months of the year that aren’t focused on lift operations, the short-story result of which is an ongoing successful evolution of many resorts from “ski town” to “year-round mountain destination.”

Easy, right? Well, not quite.

Not Apples to Apples

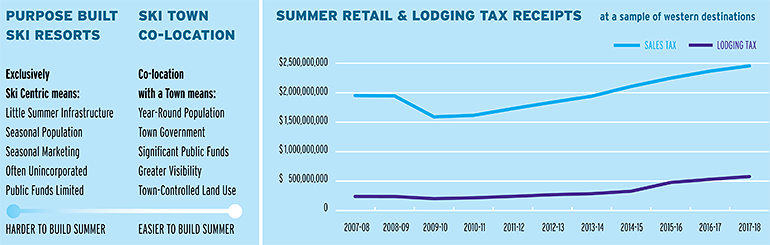

Not all ski resorts are equally adaptable. There are fundamentally two types of ski areas: those that are purpose-built for ski, typically made up of a mountain, lifts, lodging, and a base area; and those that are built around a mountain town, with all of the above, but the added benefit of a local workforce, consumer base and services, local government, and local taxes.

The data clearly show that ski areas built around a town with infrastructure are more successful (sometimes dramatically) at adapting for summer operations than those that are purpose-built. This differentiation is mainly attributable to the presence of the aforementioned benefits inherent to an established town. In short, the economy of the town is not entirely reliant on the mountain and infrastructure-specific operations, providing greater flexibility. This isn’t a fault of purpose-built resorts, just an operational reality.

Activities and Events

Among the first roadblocks to overcome for year-round business was land use. The many ski resorts operating on or adjacent to U.S. Forest Service land were limited by federal restrictions until use criteria were expanded as part of the Ski Area Recreational Opportunity Enhancement Act (SAROEA), enacted in April 2014. This made it easier for ski areas to add such destination magnets as zip lines, canopy tours, mountain coasters, and mountain biking. The result has been an added dimension to many ski towns, providing broader and more diverse revenue sources, but also creating the beginnings of summer backlash. We’ll revisit that a little later.

Some mountain towns now hold events, festivals, or celebrations, such as this 4th of July parade in Crested Butte, Colo., every weekend in summer to draw destination visitors.

Some mountain towns now hold events, festivals, or celebrations, such as this 4th of July parade in Crested Butte, Colo., every weekend in summer to draw destination visitors.

In addition to more activities, mountain towns are refining their events. Yes, prior to 2009, cultural events such as film festivals, food and drink events, and concert series drew steady crowds to mountain towns. The maturation of these events, and the addition of new ones, have contributed to growth and helped to fill in visitation gaps. Some towns now offer major events every weekend from early July through Labor Day.

So, what’s the impact of these events and recreational activities? That depends on how you want to define “impact.” In this first article we’re going to touch on the impact on the traditional—or professionally managed—lodging industry in western mountain towns. We’ll be visiting other “impact” definitions—such as the impact on housing base, backlash from local communities, infrastructure, and price tolerance—in future issues.

Lodging and Head Counts

Let’s start with the most obvious: town visitation. While visitation itself is an absolute number, measured in heads, that number is very difficult to quantify, so we’ll turn instead to lodging occupancy rates. Occupancy rates are a good indicator of visitation based on known qualities of a lodging stay, such as the average number of persons on a summer guest folio (2.5 across the western mountain industry), knowing the total number of room nights available across a given DestiMetrics sample and timeframe (3.92 million, from May 1 to Oct. 31, 2018, at western resorts), and doing some math.

Bringing the summer 2018 occupancy rate of 48.3 percent into the equation (up from 47.2 percent in 2017), there were 1.89 million room nights booked over the summer season, and 4.73 million visitor days. That’s up 1.4 percent from summer 2017’s total of 4.66 million visitor days. This is a pattern that has repeated itself since summer 2013, with a cumulative effect of an additional 413,383 visitor days added since then. Keep in mind that this represents overnight stays, not day visitors, which vary widely by destination but can easily double the number of guests in a town on any given day.

Our next definition of “impact” ought to include room rate, which is the most easily measured expense of a guest stay. In a consumer market driven by supply and demand, higher occupancy rates translate to higher room rates, which have revenue implications. We can choose to think of revenue purely from the perspective of the lodging industry, but I prefer a more holistic approach, looking instead at the impact on lodging taxes, which are used, at least in part, to support infrastructure, fund special events, and ensure that the Destination Marketing Organization (DMO) has the funding it needs to fulfill its mandate.

Keep in mind that this calculus of lodging taxes is exclusive of all other spending in the community by the visitor, and also ignores such esoteric considerations as “spend multipliers”—how often a dollar circulates in the community before it’s stashed under someone’s mattress (usually, about 1.7 times). Our goal here is to be illustrative, not specific.

Average daily rate (ADR) is the average price of a room per day over the course of a stay and takes into account higher and lower prices that may occur during a stay. It is exclusive of (but informs) room taxes, fees, food and beverage, and other ancillary costs. ADR is pure room-revenue.

Rates and Rates

While summer room rate has gone up only slightly relative to winter, it has gone up dramatically relative to itself. In fact, the increases in room rate during summer dwarf the occupancy gains. In summer 2018, ADR for the same set of destinations cited earlier for occupancy, was $237 per night, up from $232 per night last year and dramatically higher than the $186 rate in 2013.

FUNDS FOR GROWTH

The ADR punchline is this: room revenue, the dollars against which lodging taxes are applied, are a cumulative result of the changes in occupancy and ADR. As a result, room revenue for summer 2018 in our western sample was roughly $449 million, up from $432 million in 2017 and $321 million in 2013. That’s an increase of $16.5 million dollars from last year and $127.6 million from six years ago. That fuels lodging taxes that fund the aforementioned entities and projects.

The ADR punchline is this: room revenue, the dollars against which lodging taxes are applied, are a cumulative result of the changes in occupancy and ADR. As a result, room revenue for summer 2018 in our western sample was roughly $449 million, up from $432 million in 2017 and $321 million in 2013. That’s an increase of $16.5 million dollars from last year and $127.6 million from six years ago. That fuels lodging taxes that fund the aforementioned entities and projects.

Taking only this simple lodging and visitation component into account, there’s clear motivation for mountain town governments and constituents to drive summer business. When overall sales taxes from retail transactions are taken into consideration (see chart on p. 65), the motivation is stronger still. Since 2009, retail sales at mountain communities are up almost 67 percent, with an increase in sales receipts of more than $1 billion. That’s real money.

summer vs. winter

Though very impressive, this growth in summer visitation is relative to itself. We cannot look at these numbers without comparing them to the continued winter growth. Our next article will dive into those comparisons in detail, but in short, summer occupancy rates are the most impressive news, at 97 percent that of winter occupancy rates. A decade ago, that near-parity seemed impossible to achieve in such a short time.

At the same time, summer room rate is 60 percent that of winter, and overall revenue about 58 percent. It’s unlikely summer rates and revenue will catch up to winter anytime soon. In a nutshell, mountain resorts still rely on winter visitation for the majority of their revenue. But there is a lot more to these numbers, and we’ll dive into that next time.

Things are looking pretty good for ski areas and how they adapt to year-round destination travel markets. There have been clear successes over the past nine years, especially the past five.

The Downsides

However, there are issues facing the mountain destination travel industry in both the summer and winter seasons that may threaten the sustainability of all operations if not checked.

For example, visitation and room rate are both experiencing their own versions of pushback. The former is creating a negative response in the local community, as residents look for some down time, and the latter is driving a wedge between mountain destinations and the marketplace, making exclusivity ubiquitous.

And there are other concerns that must be addressed holistically in the community to ensure ongoing success. Changes in how the housing base is being used—and sold—are straining property managers and employers to find rental lodging for guests, while ensuring there is long-term workforce housing. DMOs are working to sustain brand image as their destinations shift from ski-centric to year-round, and also as the social marketplace bypasses carefully-managed brand messaging and takes the consumer to third-party solutions (Airbnb, VRBO, etc.) for information and booking.

And there are other concerns that must be addressed holistically in the community to ensure ongoing success. Changes in how the housing base is being used—and sold—are straining property managers and employers to find rental lodging for guests, while ensuring there is long-term workforce housing. DMOs are working to sustain brand image as their destinations shift from ski-centric to year-round, and also as the social marketplace bypasses carefully-managed brand messaging and takes the consumer to third-party solutions (Airbnb, VRBO, etc.) for information and booking.

Keeping up with infrastructure maintenance is also a challenge in many communities. Downtime for repairs is shorter, and the space between ski and warm weather visitation is getting too narrow to keep up with wear and tear. These are just a few of the issues we’ll discuss in future articles.

Growing Pains

The industry has done a good job evolving, and the successes of the summer season show that adaptability. But in so doing, we’ve created a set of consequences that require a little tweak to the mountain town genetic code, while dealing with outside forces such as the rent-by-owner marketplace, which are forcing change upon us. How we talk about and address these issues will be part of the ongoing shift to year-round mountain resorts.

Next time, we’ll discuss the nuances of comparing summer to winter, and some of the issues facing the bed base that are driving those numbers.