The future of skiing and snowboarding—and the world’s snowsports industry—will be on display when the XXIV Winter Olympics begin in Beijing on Feb. 4. Since the Chinese capital was awarded the Games in 2015, the government has put considerable resources behind building a vast infrastructure—from transportation to event venues—that will serve the country’s growing base of snowsports participants even after the Olympic flame has been extinguished.

“Without a doubt, the facilities are state-of-the-art and architectural and engineering masterpieces,” says Justin Downes, a former Intrawest executive who has been working in China since 2006 and has been intimately involved in the Olympic effort. “They are the most enviable facilities in the world. The engineering feat alone is unimaginable to most people.”

To accomplish this, organizers and site owners enlisted the expertise of several familiar resort equipment suppliers and planners from around the world. Here’s a look at how the 2022 Winter Olympics venues came together.

SUMMIT COUNTY CHINA?

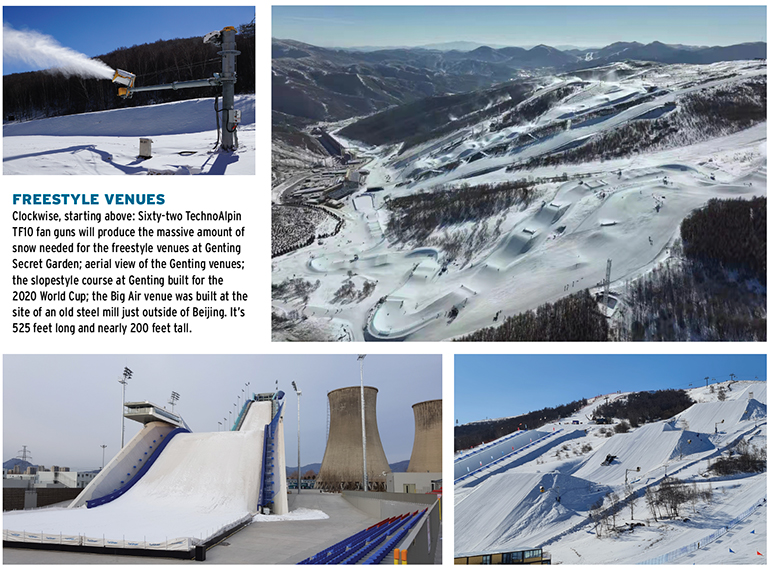

The freestyle events at the Games will take place at Genting Secret Garden Resort, located in Zhangjiakou/Chongli. Genting was already in planning and construction when the idea of an Olympic bid was conceived. The resort first opened in 2012.

Getting from Beijing to the Chongli district—home to a half dozen other ski resorts—once took more than three hours. As part of the Olympic bid, China built a high-speed train that makes the trip in 50 minutes, which many believe will be the Games’ most lasting legacy.

Game-changing access. “The transportation system is unbelievable,” says Paul Mathews, CEO and chairman of Whistler-based Ecosign, a resort planning and design firm that has handled venue design for six Olympic Winter Games. “Chongli will become like Summit County in Colorado and Utah. It will host two- to three-million skier days a year and become the center of China’s recreational ski industry, post Olympics.”

Downes agrees: “The high-speed rail from Beijing to Yanqing and Chongli is a game-changer, and now puts seven ski resorts on the doorstep of Beijing, a city of more than 23 million people.”

Downes’ Beijing-based company Access Leisure Management will oversee all of the mountain safety operations, including international ski patrol experts and equipment, at both the Genting freestyle venues and the alpine venues.

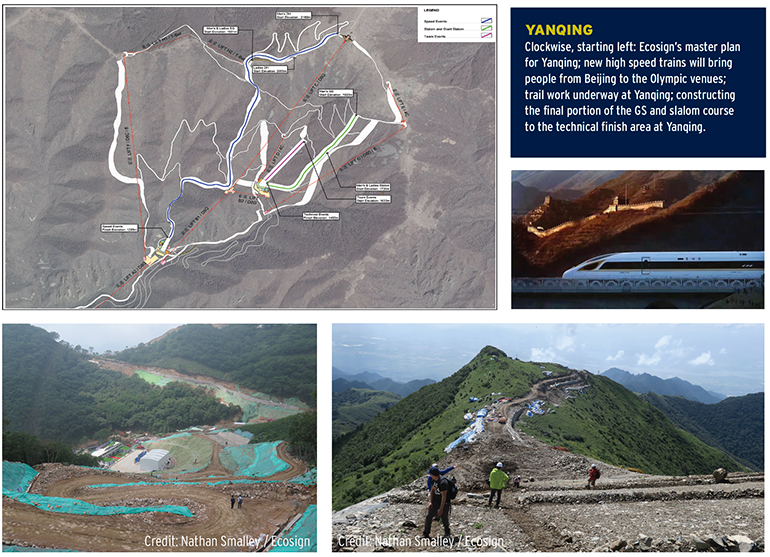

YANQING: PURPOSE BUILT

Genting doesn’t have enough vertical to host the alpine events, specifically the men’s downhill, which requires a minimum of 800 meters of vertical, so other options needed to be explored.

“The Chinese bidding committee had us look at an untouched mountain in Yanqing for the alpine events, but it was so steep, south facing—I was a little doubtful,” says Mathews. “But with Beijing money and power, we came up with the best design for the bid.”

That site is now a newly developed ski resort that will host all of the men’s and women’s alpine events. It will have two finish areas: one for downhill and Super G, and the other located a kilometer to the east for slalom and GS.

Earth moving. Both finish areas were challenging to build, says Mathews, especially the speed finish. “We had to more or less move a mountain to build the speed finish area, but it was just a soil moving exercise and we balanced the materials to build the finish zone, so it all looks quite ‘normal’ now,” he says.

For the race courses themselves, “We and the FIS designers tried our level best to simply follow the natural terrain, and on the big picture did just that,” says Mathews. “However, the site is so steep that we had to build many go-around roads and skiways, so the area got torn up more than we would normally like. We moved a lot of soil to build all of this.”

The Olympic events will be the first international competition run on the courses due to Covid.

RECREATIONAL FUTURE?

For all of its state-of-the art infrastructure, Mathews says the site at Yanqing probably won’t become a major ski destination post-Olympics because much of the terrain is simply too steep. Portions of the second section of the downhill course, for example, are about an 80 percent gradient (38.6 degrees), “so this is off limits to recreational skiers and will be challenging, to say the least, for many Olympians as well,” says Mathews.

“The challenge is, there’s not much beginner or intermediate terrain,” he says. While the parallel slalom, slalom, and GS slopes should be manageable trails for average skiers, the rest of the trails are work roads built to allow course workers and officials to move around the mountain.

Still, says Mathews, “because of the Olympics, it will get a lot of interest from tourists and sightseers who can ride the gondolas up and down.”

LIFT INFRASTRUCTURE

The new lift system at Yanqing encompasses nine Doppelmayr lifts to transport athletes and spectators from the village at the base up to the various event and training venues. The lifts include five detachable eight-passenger gondolas, two detachable six-passenger bubble chairs, and two fixed-grip quads.

One of the unique elements of the lift system is there are two pairs of gondolas: A1 out of the Olympic Village and A2, and B1 and B2. All have an uphill capacity of 3,200 pph. Each pair meets at a shared terminal, or middle station. All four gondolas have their own independent haul rope loop, allowing them to operate independently so that, for example, the mid-station is the upper terminal of A1 and the lower terminal of A2.

Flexible design. The design of the shared terminal allows each pair to be operated as one combined system, too, thanks to “a section drive-through design with a continuous station structure, connection conveyors, and lifting platforms for the connection clearance channels on the loading platform,” says Doppelmayr PR manager Julia Schwärzler.

In this configuration, passengers can ride in the same cabin all the way from the base of A1 in the village to the top of A2, passing through the mid-station without disembarking.

The B1 and B2 shared terminal operates in the same fashion, but with a much longer drive-through connection channel and an angled terminal inside the mid-station building. For easy access, the bottom terminal of Lift C, the fifth gondola (with 2,400 pph capacity), which terminates at the top of the downhill course, is located right next to the B1 and B2 shared terminal.

Function and comfort. All lifts are powered by AC drives with gearboxes and are equipped with redundant drive concepts to ensure their reliability as the primary means of transportation on the mountain.

Ironically, there will likely be few spectators during the Olympics because of Covid. But the system has been designed with the future in mind. Detachable gondolas and bubble chairs—all with heated seats—will be popular, convenient, and comfortable for tourists who are expected to flock to the mountain after the Olympics. Skiers not so much.

SNOWMAKING

The mountainous regions where the events are being held aren’t exactly powder meccas. According to the Beijing Meteorological Bureau, the mountains in Yanqing average less than eight inches of snow annually. Genting, to the north, doesn’t get much more than that. So, the alpine, freestyle, Nordic, and big air events will be run on 100 percent manmade snow produced by powerful new systems from TechnoAlpin.

“Every venue has different needs and a different climate situation,” says TechnoAlpin area manager for China Michael Mayr. “But, generally speaking, for the freestyle venue, the biathlon and Nordic venue, and the alpine venue, the climate situation for snowmaking is perfect—very cold, very dry.”

Extensive systems. To capitalize on those conditions, at the Yanqing alpine venue, the trails are lined with 170 TF10 fan guns, all spaced about 200-230 feet apart, standard spacing for fixed snow guns in China, says Mayr. Additionally, 30 V3 fixed lances cover the narrow trail from the downhill finish area to the Olympic Village.

This arsenal is fed by a primary pumphouse with 18 Caprari high-pressure pumps that send water up the hill at a whopping 17,611 gallons per minute. Then a booster station with 11 pumps (about 4,000 gpm) and a final booster with four pumps (about 1,540 gpm) distribute the water throughout the 100,000 linear feet of new snowmaking pipe.

The fully automated system is equipped with eight cooling towers, and draws from a 2.6-million-gallon snowmaking reservoir, which is fed by other reservoirs near the venue.

Optimized production. The freestyle event venues at Genting were outfitted with 62 TF10 fans and 30 V3 lances, all fully automated. The fans are spaced much tighter—115 to 165 feet apart—due to the volume of snow needed to build the courses. The cross course, in particular, needs such a high volume of snow that it has snow guns on both sides of the slope, says Mayr.

The primary pumphouse at Genting has a capacity of nearly 5,300 gpm, and the booster station’s capacity is roughly 2,400 gpm.

In Beijing, the Big Air venue—a massive structure standing nearly 200 feet tall and 525 feet long, built on the site of a former steel mill—is covered by a fully-automated system that includes seven mobile V3 lances fed by one pumphouse with a capacity of 484 gpm. A cooling tower helps to compensate for the milder climate in the city.

GROOMING

Prinoth is supplying all of the grooming machines for the Olympics to prepare the downhill, Nordic, freestyle, and big air venues.

“Prinoth has delivered nearly every kind of snowcat to the Olympics, including converted groomers to transport AdBlue and diesel, passenger transport snowcats, snowcats with cranes, and snowcats for transporting material next to the cats used for slope and course preparation,” says Prinoth head of marketing Ben Hodgson.

A total of 53 cats are on hand, including 30 Bisons and 17 Leitwolfs with winch, solo, and X (park) configurations, and six Huskys for cross country skiing and with X configurations.

Local partners. Prinoth has stockpiled spare parts at the venues and with Chinese sister company Poma Beijing, says Hodgson, noting that local partners have been invaluable to the success of the operation. “Without our Chinese team, none of this would have been possible. They have helped with the organization—especially difficult considering the strict regulations in place—and are managing the project closely.”

300 MILLION CHINESE SKIERS?

Although China has not been recognized as a major winter sports player in the past, when the 2022 Winter Games were awarded in 2015, General Secretary Xi Jinping pledged a goal of involving 300 million Chinese people in winter sports. The goal is lofty, but Downes says the Olympics have already jump started a Chinese snowsports revolution.

“It is obvious over these past several years Chinese skiers and non-skiers are falling in love with the mountains and the lifestyle attached to it. It will just take a little longer to result in the deeply embedded mountain culture that is embedded in North American and European resort towns and communities,” he says.

“The Chinese resorts are the beneficiaries of the most modern technologies given the newness of the industry and the deep pocketed investments by the government and developers,” Downes adds. “We have the most advanced snowmaking, grooming, and lift systems and the infrastructure (high speed rail, expressways, and airports) in the world to get people to the resorts.

“I see China very quickly becoming a global force in snowsports.”