The collaboration between Rachelle Leishman, sustainability manager at Brundage Mountain, Idaho, and Meredith Todd, city and sustainability planner for nearby McCall, started in 2023 with an idea. Todd had conducted a greenhouse gas inventory for the City of McCall and suggested Leishman, who was completing her masters in sustainability, do the same for Brundage. A professional relationship based on resort-municipal collaboration and information-sharing was formed.

“We realized we could really align our powers and start making steps towards sustainability at both McCall and Brundage,” says Leishman.

Broadening the impact. Since then, they’ve worked together on housing shortages, transportation needs, wildfire mitigation, and climate resiliency planning. The partnership has had a regional impact, too, something they discussed as joint panelists at the 2024 Mountain Towns 2030 Climate Solutions Summit (MT2030), in Jackson, Wyo. There, they shared insights about how resort–municipality partnerships can help both entities navigate political and regulatory frameworks and drive community and regional climate action.

“I’ve gotten great feedback,” says Leishman. “A lot of ski areas face similar challenges in being able to drive innovative solutions.”

Communication matters. MT2030 director Chris Steinkamp says he’s seen an uptick in such collaborations between resort and municipal sustainability teams. “If not a partnership,” he says, “at least a conversation.”

That dialogue is critical, says Steinkamp. “The reason resorts are such an integral partner in MT2030 is that mountain communities are not going to get to net zero without resorts playing a big role in the conversations. Resorts have a real seat at the table.”

Brundage: Municipal Collaboration

In just a few short years, Brundage and the City of McCall have built a cross-county partnership to take on challenges ranging from wildfire preparedness, water quality, housing scarcity, and demand for service workers, says Leishman.

The collaboration has grown to include multiple stakeholders, helping to secure funding and develop long-term solutions that benefit both the resort and the broader community.

For example, one impactful initiative is hoping to secure more than $20 million in grant money to identify and tackle wildfire risk under the Southwest Idaho Landscape (SIL) project. The initiative would benefit several surrounding towns and nearly a million acres in the Boise and Payette National Forests. The various stakeholders continue to work together to identify priority projects for wildfire mitigation and other project areas within the SIL, and to identify other opportunities with local or state government.

Housing and transit. Housing is another critical issue. Brundage and McCall have advocated for affordable housing solutions, not just for resort employees but also city residents, particularly local families with school-aged children. Leishman says Brundage has “taken a bigger seat at the table” regarding housing since partnering with McCall and is now working with the U.S. Forest Service to find additional housing solutions for both resort and Forest Service employees in future years.

To reduce emissions and improve public transit, which does not receive dedicated state funding in Idaho, the resort also works with the nonprofit Treasure Valley Transit to help fund a free shuttle service for employees.

Bigger steps. Brundage is also working under the City of McCall on a comprehensive climate action plan as well as participating in a larger climate resiliency plan that’s being developed with input from the City of Boise, Boise State University, University of Idaho, St. Luke’s McCall Medical Center, and others.

“We are all developing our own internal plans and presenting them to each other to create a full climate resiliency plan,” says Leishman. “We all believe that aligning our powers and collaborating will create bigger impact and have the best outcomes for our communities in long-term planning and resilience.”

The groups get together to share data and brainstorm initiatives for sustainability solutions, community engagement, health equity, public land partnerships, and other topics that factor into the climate action and resiliency plans. At the last meeting, they looked at existing programs related to environment and food security.

“We each have active resiliency efforts and active data sets with community stakeholders at the table,” says Leishman. “Ultimately, we will have one working document with efforts focused on McCall and Boise.”

Follow the leaders. Leishman says other mountain resorts that face the same challenges can adopt a similar approach to tap the resources at their disposal. “If you are looking for partnerships, reach out to your local stakeholders that are involved in your ski area and find ways that you can collaborate,” she says. “If there’s data available, do your best to share it to make data-driven decisions. Collaboration means coming to the table and homing in on how we can find a solution and a pathway forward and being able to hear the other side. Even if you don’t see eye-to-eye, there are ways to create impact.”

Left to right: Brundage Mountain, Idaho, worked with the town of New Meadows to acquire this building and fully renovate it to create affordable housing for staff; Brundage Mountain, Idaho, collaborated with a nonprofit transit provider to fund a local shuttle service.

Left to right: Brundage Mountain, Idaho, worked with the town of New Meadows to acquire this building and fully renovate it to create affordable housing for staff; Brundage Mountain, Idaho, collaborated with a nonprofit transit provider to fund a local shuttle service.

Bridger Bowl: Research and Resilience

At Montana’s Bridger Bowl, participation in local, regional, and state-level groups allows staff to stay connected with community needs and explore collaborative projects, says Bridger Bowl sustainability director Bonnie Hickey.

Educational effort. For example, a partnership between Bridger Bowl, a watershed group, and local government led to the installation of interpretive signage to promote environmental education. More than 5,000 annual participants in the resort’s Ski PE program have been exposed to the graphics, which target water conservation, climate change, and other environmental topics, and they’re also used during staff training and public presentations.

Community collaboration. A larger initiative with the City of Bozeman and Montana State University aims to secure a grant to increase climate resilience to excessive heat and poor air quality, which would benefit outdoor workers in vulnerable populations.

The collaborative effort would help identify resources that could strengthen resilience capabilities, such as buildings with air purification that could serve as respite centers during a crisis, back-up generators for snowmaking machines that could aid in wildfire suppression, or sources to provide box fans and filters to low-income families.

Bridger Bowl is collaborating with the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Air Quality Division to enhance on-the-ground local education about the initiative, says Hickey. “Ski areas serve as trusted partners with significant public outreach and education expertise, making them valuable contributors to these initiatives.”

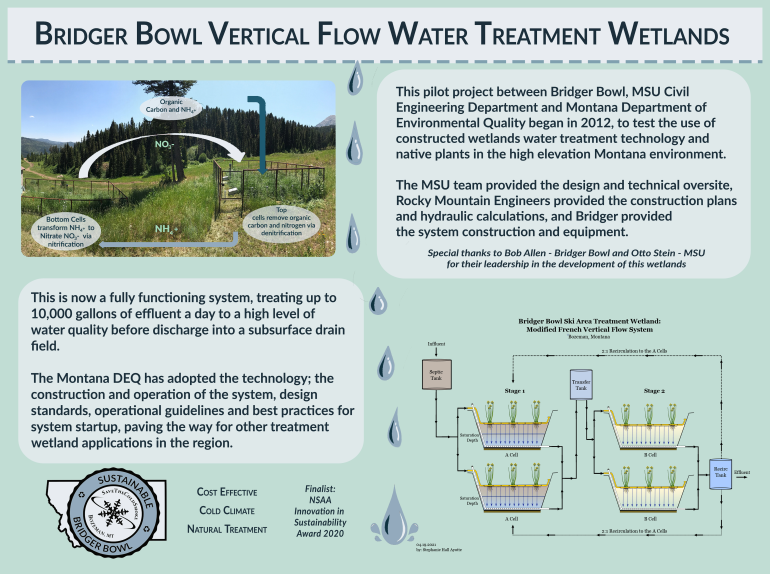

Statewide action. One of Bridger’s most intensive collaborations has been the vertical flow water treatment wetlands project—funded by Bridger Bowl and a grant from the DEQ, says Hickey. The project is engineering an ecological approach to wastewater through the use of constructed wetlands with sand-and-gravel beds and piping that uses intermittent dosing to benefit different microorganisms.

Led by a Montana State civil engineering team and Bridger’s facility manager Bob Allen, who became the resort point person after MSU first reached out, the project aims to prove the viability of this low-energy wastewater treatment system in cold, high-elevation climates.

The success of the research ultimately has led the DEQ to approve this type of system for use in Montana, where Hickey says many businesses seek to improve wastewater system performance. Bridger continues to sponsor the research, with the resort’s facilities team collaborating on ongoing maintenance and testing.

Strength in numbers. Such partnerships can help divide a heavy workload as well as bring in outside expertise, says Hickey.

“We are all so busy in our ski area roles that it is hard to be the sole resource on a project,” she says. “But people want to help us be successful, and I look everywhere to network—to people in similar positions, in different industries, in government agencies, and in other nonprofits. I look to our vendors for collaboration on solutions as well.”

Advocacy: A Systemic Solution

While on-the-ground sustainability projects are essential to driving climate solutions, snowsports areas are increasingly recognizing that policy advocacy is equally important to creating a climate-resilient future.

Advocacy work is about driving a “systemic solution,” says Steinkamp, who notes advocacy sessions at the 2024 MT2030 summit were well attended. Many ski areas and state associations are “doing advocacy well,” he adds, including Ski New Hampshire and its member resorts, Aspen Snowmass, Colo., Taos Ski Valley, N.M., Arapahoe Basin, Colo., and Sun Valley, Idaho, to name a few.

“How do we focus our voices as businesses to drive climate policy?” Steinkamp asks. “There’s a lot of that kind of thinking going on at ski areas.”

Arapahoe Basin: National and Local Policy Action

At Arapahoe Basin, sustainability manager Mike Nathan says advocacy is a “huge central piece of our sustainability program and becomes more so every year.”

A-Basin is a founding member of the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA) Climate Challenge—a voluntary program that helps participating ski areas inventory, target, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The area has also partnered with industry groups including NSAA and Protect Our Winters on state-level advocacy as well as trips to Washington, D.C.

Connections are helpful. “We’re not lobbyists, so it’s good to have those connections,” says Nathan. “We get directly involved at the state and county levels, and we’ve got good relationships in the Colorado Senate and House at the state level.”

In March, A-Basin director of planning and development Tony Cammarata traveled to Washington, D.C., with NSAA to advocate for, among other things, federal tax incentives for electric vehicles and renewable energy. The trip resulted in Republican senators, including Colorado’s Jeff Hurd, signing a letter of support for IRA tax credits.

The resort has also been “very vocal” advocating for the SHRED Act, which would allow National Forests to retain a portion of the annual fees paid by ski areas operating within their boundaries to use for various improvements to processes, management, and more.

Go big. A-Basin is active in broader sustainability advocacy networks, too. The resort collaborates with Ceres, a nonprofit focused on lobbying for corporate climate action, and America All In, a coalition that advocates for strong climate policies and offers a free newsletter full of research, event, and advocacy opportunities.

“There are a lot of people who can provide you what you need to get started with actions,” says Nathan. “Industry groups or state-level advocacy groups are great resources.”

A-Basin leadership is also outspoken on critical issues and has started to submit opinion pieces on climate-related topics to state and regional news outlets. For example, A-Basin COO Alan Henceroth co-authored a 2023 op-ed with Aspen Skiing Company CEO Geoff Buchheister in support of the Colorado Clean Car Rule and electric vehicles, which was published in the Denver Post.

“Though it’s impossible to track exactly what [op-eds] accomplish, it’s a way to be heard,” says Nathan.

Bridger Bowl: Local and State-Level Advocacy

At Bridger Bowl, Hickey says there is a “growing need” for advocacy, “resulting from changes in state and federal administrations as well as increased demand for our voice as a spokesperson for the outdoor recreation industry.”

Outside resources. Bridger relies on its state government’s online bill tracker and subscribes to nonprofit newsletters, including the Montana Environmental Information Center (MEIC) and the Montana Renewable Energy Association, which provide weekly calls to action. Registering with the State of Montana’s website for public commentary and using the bill tracker provides direct insight into a bill’s progress from committee to the Senate or House, as well as which representatives to contact with concerns.

She says when a bill to outlaw cloud seeding was introduced with language that could have been interpreted to include snowmaking, MEIC alerted her, so she quickly brought it to the attention of the Montana Ski Areas Association.

Gaining leverage. “Engaging with these groups allows us to leverage their experience and strengthen our collective advocacy,” says Hickey. “Supporting their public events, tabling alongside them, and taking direct actions, such as signing petitions to the Public Service Commission or commenting on bills, is crucial. The combined efforts of nonprofits, businesses, and the public send a powerful message.”

Other regional groups, such as Climate Smart Montana, Gallatin Watershed Council, the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, and Gallatin Valley Earth Day, offer a strong network for education, outreach, and mutual support, Hickey says.

Political action. Both Bridger and A-Basin actively engage with policymakers through letters and phone calls to explain the positive impact of proposed bills. At Bridger, Hickey takes the lead on these projects with sign-off from resort management.

Recently, Bridger teamed with Montana’s Discovery Ski Area and Big Sky Resort to join public outreach efforts in support of a community-shared solar bill being sponsored by a local legislator. The three drafted a joint letter of support, and Discovery VP Ciche Pitcher presented it in person before the Senate Energy Committee. “He highlighted the bill’s key business benefits, and our combined efforts helped move the bill successfully through committee and on to the Senate,” says Hickey.

Building Capacity

At the end of the day, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

“So much of our work is collaborative in nature,” says A-Basin’s Nathan. “Without being too cliché, none of our environmental initiatives would be impactful if we were doing them by ourselves.”

Steinkamp echoes the sentiment. “Our role [at MT2030] is to help mountain communities tackle climate change effectively and quickly and build capacity so that every mountain community of any size can effectively tackle climate change,” he says. “Some mountain communities have the resources to deploy solutions right now, but others might need some help. Our goal is to build capacity in those communities through collaboration.”

And of navigating the country’s new political climate? “Climate action really has to start at the state and community level—that’s us,” he says. “It’s even more important that we do that now, because who else is going to?”