The simple secret of Whistler Blackcomb’s summer ops success: maximize the experience of your physical environment. It helps to have a couple of spectacular alpine peaks, of course, but two principles reign regardless: work with your environment, and create the biggest wow factor you can with it. That applies no matter how big or small your area is.

To do that, though, requires understanding your audience. And the summer crowd is entirely different from winter.

To grasp how Whistler Blackcomb’s summer ops came to embody these principles, SAM spoke with the resort’s leadership, as well as two longtime insiders who helped shape the resort’s approach from the beginning: Arthur De Jong, former mountain planning and environmental resource manager, and Rob McSkimming, former VP of business development, both of whom were with the resort from 1980 through the 2010s.

What Summer Guests Want

“The summer guest can be quite different, and understanding the experiences they’re looking for, and the ways to communicate to those guests, is a bit of a transition,” says McSkimming.

Lookers and doers. “We segmented the audience into lookers and doers,” he says. “Probably 80 percent of sightseeing visits are what we would call lookers. These are people that aren’t that familiar with mountain resorts, or with lifts, but are really taken by the power of that experience, because it’s not one that they participate in all that often.”

And that’s important because scenic lift rides are, “by far, the biggest part of the business, and one that continues to have the most potential,” says McSkimming. “If you’re looking to build a viable four season business, that component is the secret to getting yourself there in a significant way.”

De Jong adds, “In our surveys, any guest who went up the mountain in the non-winter rated the overall resort experience better. That was a constant.”

The doers, says McSkimming—who are often skiers and snowboarders in the winter—“are pretty active people when it comes to mountain recreation.” Aside from the Whistler Mountain Bike Park, “doers gravitate to the hiking side of things and trail running, that sort of thing.”

Accommodating all. “We would always try to make sure that in our planning, we were taking care of both groups,” he adds. “And that can be a struggle, because most resorts have grown up as an active, winter-based activity.”

To cope, Whistler created a summer team consisting of employees who were dealing directly with guests throughout marketing, booking, arrival, dining, etc., McSkimming says. “We made sure that every aspect of what we delivered as an experience was represented at that table. Having that really focused summer team was a good way to understand those [summer] people and be able to guide them,” he says.

Something for everyone. Whistler is close to the diverse metropolitan area of Vancouver, so to meet the demands of a broad audience, the resort offers a wide array of summer activities, from zip lines, Jeep tours, and a via ferrata to the sightseeing activities. The sights are largely accessed from the Blackcomb, Whistler, and Peak2Peak gondolas, which form a triangle up and between the two peaks, and the Peak Express chair. These serve more than 50 km (about 30 miles) of trails on both mountains, plus guided bear viewing tours, and seasonal snow corridors carved through remaining winter snowpack on Whistler. The peak is also home to the Cloudraker Skybridge and Raven’s Eye viewing platform.

For more active visitors, the Whistler Mountain Bike Park offers a massive network of lift-served downhill trails. Elsewhere in the community are the Vallea Lumina night walk, the unique Scandinave spa, four golf courses, and water sports on the region’s lakes and rivers, among other options.

There was some concern in the community, and probably within the mountain company, whether the softer adventures on the mountains were on brand at the start. Their popularity showed either that they were, or that they expanded what that brand encompassed.

In developing year-round activities and attractions, “We consider non-skiers, families, and accessibility beyond our core guests,” says Whistler Blackcomb COO Belinda Trembath. “For the near term, a lot of focus is being placed on collaborative activities and events with partners and on-mountain community programming, as well as continued improvement on wayfinding and interpretive signage.”

Left to right: The Whistler Mountain Bike Park is the most visited bike park in the world with more than 100 km (about 62 miles) of trails ranging from mellow beginner terrain to expert lines; CrankWorx, a two-week mountain bike festival, draws thousands to the bike park every year.

Left to right: The Whistler Mountain Bike Park is the most visited bike park in the world with more than 100 km (about 62 miles) of trails ranging from mellow beginner terrain to expert lines; CrankWorx, a two-week mountain bike festival, draws thousands to the bike park every year.

Whistler Bike Park

The bike park is Whistler’s best-known summer activity within the resort business. And it has played an important role in establishing Whistler’s summer visibility. It does many times the visits of any other bike park in the world, and was the launch pad for CrankWorx, a huge two-week mountain bike festival that has since spawned a world tour.

“The Whistler Bike Park was really in the center” of a rapidly growing freeride mountain bike scene, says McSkimming. “And that energy drove Whistler to build the kind of trails that would establish an event like CrankWorx.”

Since opening in 1999, the bike park has grown from a single zone beneath the Whistler Village Gondola into four distinct areas: Fitzsimmons, Garbanzo, Whistler Peak, and Creekside. With more than 100 km (about 62 miles) of singletrack, it’s the largest lift-accessed bike park in North America.

Extreme terrain and pro lines are “part of the success here and at a lot of other bike parks,” says McSkimming. “But the key to the future is, it is a family sport. Once families have exposure to it, it’s much the same as skiing and snowboarding. You’ve got kids in programs throughout the summer, and everybody’s doing it together, and it becomes part of that family experience.”

A successful bike park needs a smooth progression in trail offerings for everyone from beginner to MTB hero. “We consider every aspect of rider ability and experience—from the first time in the park to the best riders in the world—and refine the park to keep them coming back,” says Wendy Robinson, Whistler Blackcomb senior manager, planning and business development.

Imagining Summer Ops

The bike park isn’t for the lookers. So, how do you proceed on plans for the bulk of the summer guests?

First, highlight your resort’s natural assets. “I think that’s a key to any resort,” says De Jong. “You have to optimize them, and it doesn’t necessarily cost a lot. Be creative, be explorative,” he advises.

The wow factor. Think of it as adding the wow factor, says McSkimming. “Most resorts have lifts that get you to a pretty cool place, but how do you turn that cool place into something that’s way more powerful? It could be through structures, interpretive elements.”

That’s what Whistler Blackcomb did. It added a well-thought-out system of hiking/sightseeing trails high up on both mountains. On Whistler, for example, there’s a network of trails right off the Peak lift, which also accesses the Cloudraker Skybridge, installed in 2018.

“It’s kind of like developing a ski area with green, blue, and black [walking paths and hiking trails],” says De Jong. “Rather than just hitting the ridgeline, we built the trails along the ecozone where the forest subalpine hits the alpine. Every twist, every turn there’s a different viewscape and wayfinding, there’s a story. We’re highlighting all the natural assets.”

Accessible, by design. “About 70 percent of guests won’t go more than maybe 500 meters from the top of a lift station, according to our surveys,” he adds. “So, the first loop out takes them about 500 meters to a natural area where you cannot see any ski area infrastructure. This can be an adventure for those unfamiliar with being on a mountain,” and is close enough for an easy return to the lift, if needed.

From that 500-meter point there are some blue trails “that maybe are an hour to two hours long,” he continues. “So, for the Sunday hiker, there’s suddenly a whole venue of very natural experiences. These trails are really thought out in terms of making you feel like you’re in nature and not a ski area. You can’t see a lift at all, or any infrastructure.”

For the more ambitious, there are the black diamond trails, which are day-long hikes.

The payback’s crazy, says De Jong. “Relative to a half million dollars [invested in trails], it probably earns us a couple million dollars a year. Once you give people a special experience, they want it again and they come back every year because they can’t find that type of experience somewhere else: A lift that takes them into the alpine, and their whole experience remains in the alpine where they want to be. There’s no big effort getting there, and then they’re given a trail experience which is exceptional.

“These trails have the highest ROI of anything we’ve done because they didn’t cost much to build, and they were done with thought behind them.”

Amp up the adventure. And there are ways to boost the return further, like the Skybridge. “If you can afford a key piece of infrastructure that is aesthetically dynamic, and highlights the visual quality of your natural assets, grab it,” De Jong advises.

De Jong admits that the Skybridge was a big-ticket item. “And there was a lot of cynicism about us building it,” he says. “The first year we operated it, we added over 100,000 sightseeing visits. Its ROI was healthy from the get-go.” On a sunny day, the bridge is as busy as a boardwalk at the seashore.

Is something like that affordable for most resorts, though? Maybe, maybe not. That’s where creativity and opportunity come into play. “A suspension bridge, if you’ve got the right natural features, doesn’t cost that much,” De Jong says. Plus, “the cost of construction of a hiking trail is nothing,” he adds, a tiny fraction of what a new lift costs.

For De Jong the key question is, “What can you do at the least cost to showcase your natural assets?”

Left to right: The Peak2Peak gondola is an attraction in and of itself; Construction of the Raven’s Eye viewing platform.

Left to right: The Peak2Peak gondola is an attraction in and of itself; Construction of the Raven’s Eye viewing platform.

The Climate Imperative

Climate change adds another imperative for summer operations. “Given the continued impact climate change is having on the outdoor sports industry, we anticipate summer activities becoming a more prominent and popular offering at Whistler Blackcomb and mountain resorts around the world,” says Robinson.

The a-ha moment. Environmental stewardship has been part of the resort’s planning process for 30 years, says De Jong. As mountain manager at Blackcomb in the early 1990s, De Jong was at the center of a fuel spill turned environmental public relations nightmare. A year later, a glaciologist helped him become aware of how rapidly the glacier atop Blackcomb was shrinking. “This is going to take down our industry,” he thought.

So, De Jong went to Hugh Smythe, at that time the president of Blackcomb. “I said, ‘We’ve got a problem. It’s called climate change. We’re going to have to rethink our master plan.’ And he said, ‘Well, get to it, then.’”

De Jong looked to the Scandinavian countries for ideas, since they were doing the most in terms of energy efficiency and climate issues at the time. His aim was to reduce the resort’s environmental impact, and more importantly, figure out how Blackcomb (and later the merged Whistler Blackcomb) could become a model for other businesses and industries worldwide—a role De Jong believed would have a much greater impact.

As leaders in the movement to combat climate change, he says, “Our responsibility is to showcase and respect nature; it’s interesting how economically successful it can become as well.”

Planning for change. Almost every winter resort will ultimately have to confront climate breakdown. “Climate change is this big, audacious change that is very much happening and accelerating,” De Jong says.

“[You need to] find out what it’s doing to your operation. Are you going to have snow in 20 years, or 30 or 40? How quickly do you need to adapt? How much longer can you be resilient simply as a ski area? What window do you have to build the non-skiing experiences?

“There’s costs involved, and you want to spread them. You’ve got to make the economics work. What is doable in the short term to penetrate the non-skiing markets? That’s going to vary depending on whether you’re rural or are next to a large or metropolitan population.”

Master Planning for Summer

To take advantage of summer, a resort “needs a full on, phased, A to Z summer master plan,” says De Jong.

Typically, summer plans are not as thorough as winter’s. “Think hard about all the things that you can do,” he urges. “What should come first? What is financially possible? How do you phase?”

And in the process, design the summer look and feel comprehensively. Oftentimes, summer at mountain resorts means an array of activities are plastered onto the winter facilities, and it has a “skiing lite” look. “You still feel like you are at a ski area,” De Jong says.

Make summer special. Consider “the overall impression that you’re making,” says McSkimming. “What’s the finish look like when you get off the lift? Is your signage plastered over winter signs for summer?

“When people get to a high part of the mountain, they’ll just walk to the highest point. It’s human instinct. By doing something in and around that place, because that place has power, that’s something that can take the experience you’re offering to that next level.”

It’s important for summer, says De Jong, “to master plan the guest experience—an intentional experience that is unique to the non-winter months.”

Partners help. “Promoting Whistler as a summer destination is an effort done in collaboration with our resort partners,” says Robinson. “We work closely with many third-party businesses that operate on Whistler Blackcomb, including Zip Trek, Mountain Skills Academy & Adventures, and Canadian Wilderness Adventures to name a few. ... It takes a unified effort and a sharing of resources to help market, promote, and deliver a unique, world-class and unforgettable summer experience.”

Even with that unified approach, there’s work to do throughout the winter resort industry—and even at Whistler Blackcomb—to make summer ops as special as winter.

“We’re not there yet,” says De Jong. But Whistler Blackcomb showcases several paths resorts can take.

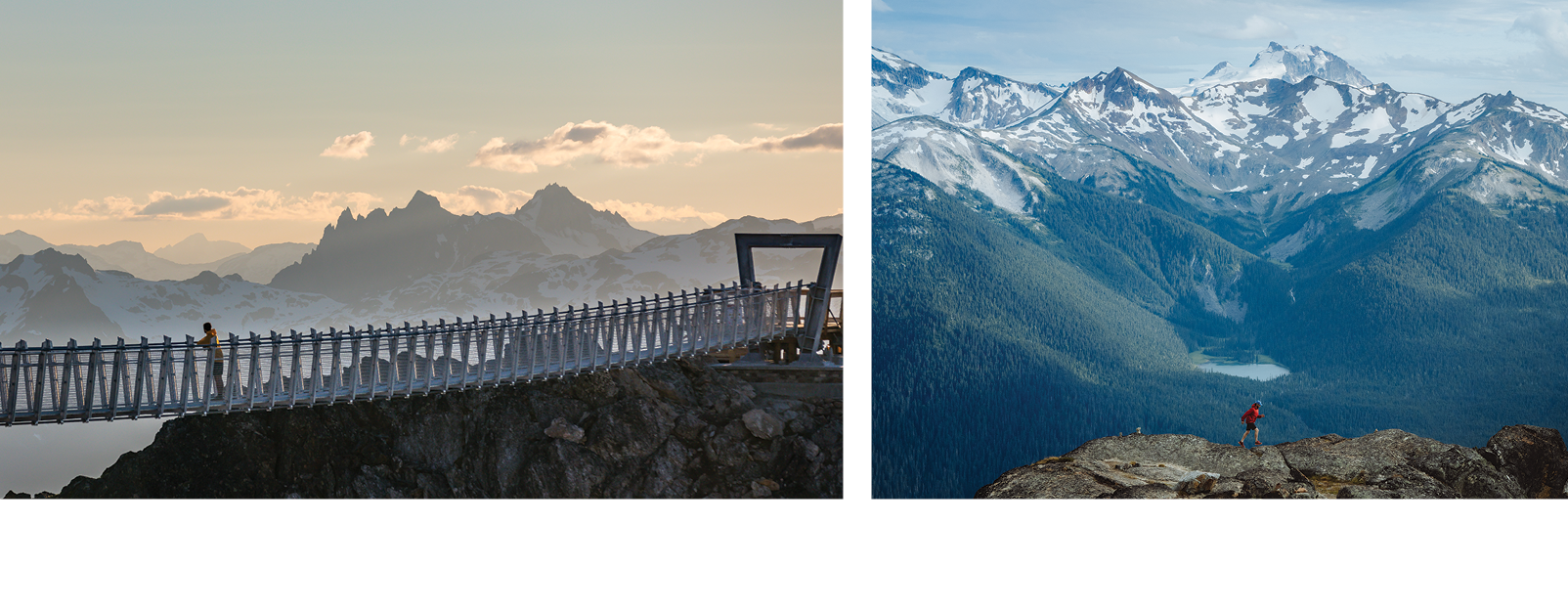

Left to right: Cloudraker Skybridge, an attraction that added 100,000 sightseeing visits in its first year alone; Whistler Blackcomb’s hiking trails were thoughtfully designed to highlight natural features.

Left to right: Cloudraker Skybridge, an attraction that added 100,000 sightseeing visits in its first year alone; Whistler Blackcomb’s hiking trails were thoughtfully designed to highlight natural features.

Community Relationships

The town of Whistler has grown to become one of the larger resort communities in North America. It can encompass 50,000 residents and guests in winter. While the town and resort have not always been united in their vision, the continued success and development of a thriving summer business has proved the value of cooperation.

As the resort developed its summer plan and began attracting more visitors, it benefited the entire community. “Everybody in the business community was definitely interested in being able to establish themselves on a more year-round basis,” says McSkimming.

De Jong, who was often the point man on resort developments and has been a town council member since 2018, advises resorts to get actively involved in the community—and to do it before you need something from the town. “Don’t just talk about stuff, fix stuff. Build trust,” he says. “Give, give before you ask.” So that when you do ask, people will be ready to listen.

Want to learn more about optimizing summer ops? Check out SAM’s 2025 Summer Ops Camp at Whistler Blackcomb, Sept. 2-4, for firsthand insights from operators and experts and hands-on experience with successful programming. Visit: saminfo.com/summer-ops-camp