The Great Salt Lake is shrinking. Snowbird president and general manager Dave Fields, who grew up in the basin, recalls annual elementary school field trips to the lake, where he and his classmates would float on their backs in the vast inland sea and return to the bus itchy with salt-crusted skin. The site of that annual pilgrimage is now surface crust.

Over the past 40 years, as the lake’s water levels have fallen and its surface area has diminished, more than 800 square miles of lakebed has been exposed. That’s more than half the size of Rhode Island. When wind kicks up over those exposed sediments, it carries dust, some of it containing naturally occurring heavy metals and toxins from industrial activity, into the same valley where thousands of people live and recreate, up into Little Cottonwood Canyon and onto the slopes of Snowbird.

The Great Salt Lake effect dumps enviable amounts of snow into the Wasatch Mountains, but that brown dust carried on the wind also causes the snow to absorb more sunlight, melting it faster by a measure of weeks. That’s a problem, as far as Utah ski areas are concerned; less water in the Great Salt Lake equals less snowfall and more snow melt.

But this is not a story about powder, or even about preserving winter.

It’s a story about how climate impacts show up in ways that have nothing to do with snowfall totals—and how ski areas are responding by expanding the scope of their climate work beyond their boundaries, operations, and even industry.

Snowbird: Climate Change as Public Health Crisis

Great Salt Lake looms large in the basin. At 1,700 square miles currently, it is the largest inland body of salt water in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth largest terminal lake in the world. A remnant of the Late Pleistocene era, Great Salt Lake remains a vital part of Utah’s ecosystem and now, its economy. One million migratory birds depend on it, and it generates more than $2.5 billion in annual economic activity, according to a 2023 Brigham Young University study. On inversion days, dust and pollution from the lake settle over the valley like a lid. On clear days, you can see the water from the Wasatch.

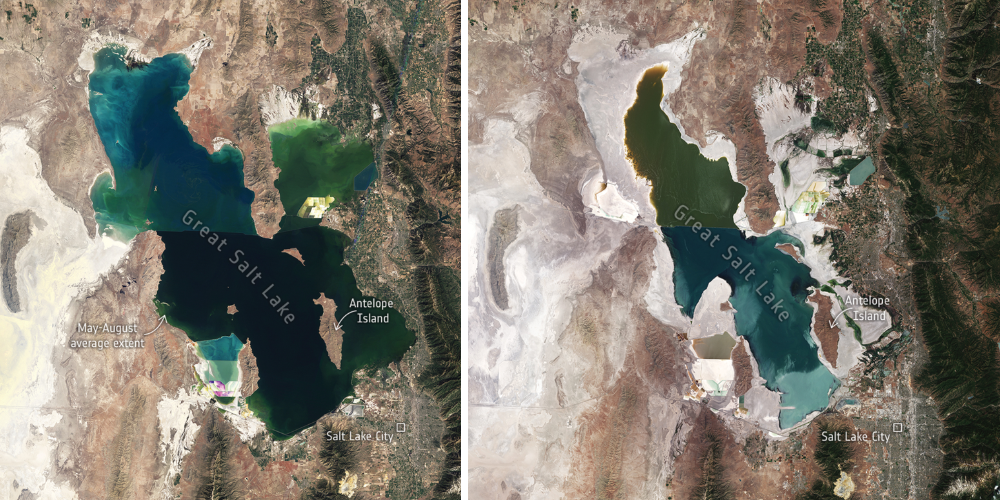

A visible concern. Unlike, say, the melting glaciers of Greenland, Great Salt Lake—which hit a record low elevation in 2022, shrinking it to just 888 square miles of surface area—is “not out of sight, and definitely not out of mind” for Utahns, says Snowbird sustainability and water resources director Hilary Arens. It is a visible existential threat.

“If that lake dries up,” says Fields, “we have an ecological problem, an economic problem, a public health problem, and a reputational problem.”

The stakes are personal and professional, he says. “I want to live in Utah. I want to ski powder.” But also, two of the four people in his household use inhalers for asthma—and as temperatures rise and the lake’s surface area shrinks, the dust storms and pollution will only get worse.

For all these reasons, Snowbird has felt it imperative to put its time, money, and influence behind a multi-coalition effort to save Great Salt Lake. “We use our resources, both financial and the reach we have, and we support scientific research, not just because it is impacting our snow and runoff is happening earlier,” says Fields. “It’s about the health of our children and one day our grandchildren, and letting them live in the cleanest air possible.”

Education. One critical step in that effort was partnering with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a longtime steward of the lake and co-manager of the $40 million Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Trust, to launch an education series, which kicked off in 2019 and then relaunched in 2022 after a Covid hiatus.

The Great Salt Lake in 1985 at its most recent high-water mark (left) versus the 2022 low point (right). Lowering levels have set off alarms in the Salt Lake community, the state of Utah, and at Snowbird. Credit: USGS with ESA mods.

The Great Salt Lake in 1985 at its most recent high-water mark (left) versus the 2022 low point (right). Lowering levels have set off alarms in the Salt Lake community, the state of Utah, and at Snowbird. Credit: USGS with ESA mods.

The annual events take place mid-morning in the Cliff Lodge ballroom, where locals, guests, employees and other stakeholders—representatives from the Forest Service, the Great Salt Lake Commission, Salt Lake County, and the Salt Lake City Division of Water Quality, to name a few—gather to learn about the shifting landscape from scientists, water managers, and researchers who explain dust-on-snow effects, changes in mountain hydrology, the science of Great Salt Lake’s decline, and the public health risks that come with a shrinking terminal lake.

Snowbird GM Dave Fields (center right) joins a panel convened for the resort’s ongoing lake-focused education series.Attendance has grown over the years, with some events drawing more than 200 people. Snowbird’s social media promotion of the events can reach hundreds of thousands more.

Snowbird GM Dave Fields (center right) joins a panel convened for the resort’s ongoing lake-focused education series.Attendance has grown over the years, with some events drawing more than 200 people. Snowbird’s social media promotion of the events can reach hundreds of thousands more.

Being the catalyst. On paper, the education series is a modest public program. The direct cost of each presentation is about $5,000 (so, Snowbird is about $25,000 all in so far, not including donated labor and meeting space). But it represents something larger: a ski area using its platform to convene a statewide conversation about health, resilience, and responsibility. Arens describes the work as both educational and connective—an effort to bring climate science into a space where people already feel tied to place.

Snowbird’s role in this work extends beyond hosting conversations. The educational effort is backed by a substantial financial commitment from the Play Forever Foundation, the charitable arm of Snowbird’s parent company Powdr, to TNC’s Great Salt Lake programs. Snowbird is both a contributor to the foundation and was instrumental in directing its support toward TNC’s work.

Additionally, the mountain sits at the upper end of the Great Salt Lake watershed, and its winter snowmelt eventually feeds into the Jordan River, one of three Great Salt Lake tributaries. That upstream position drew the resort deeper into basin-wide water concerns. “We recognize our effect on the lake and the lake’s effect on Snowbird,” says Arens.

While the educational talks at Snowbird helped make that relationship more visible, visibility alone won’t produce the scale of change required to save Great Salt Lake.

That recognition, combined with rising statewide concern, led Powdr co-owner David Cumming to help create the Great Salt Lake Alliance, an effort to align the many organizations working on—or with a stake in—the crisis. The alliance, says Arens, takes “the idea of educating and advocating for the Great Salt Lake further, using not just Snowbird’s voice or Powdr’s, but amplifying the conversation within the state of Utah.” » continued

Policy progress has followed as awareness and advocacy about the shrinking lake has grown over the last four years. Among several key bills, one clarified “beneficial use,” allowing agricultural water-right holders to let water flow to the lake without risking forfeiture of unused shares (ag is the largest upstream water consumer in the Great Salt Lake watershed). The state also created major matching funds for wetland protection (“one of the best ways to conserve water,” says Arens), and increased support for scientific monitoring and remediation. These early steps reflect the kind of structural changes Snowbird hoped its educational work would support.

Keeping the momentum. Even with those wins, the work is vulnerable to shifting public opinion. Two big Utah winters temporarily raised lake levels, and Fields worries about complacency. “[Now,] people have the false impression that it’s not such a crisis,” he says. “[But] we’re already lower right now than we were a year ago.”

With the 2034 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics approaching, urgency is sharpening again, though. “Quite honestly,” says Fields, “the 2034 Olympics coming to Utah is the best thing that could happen to the lake.”

The same lake-related concerns that threaten the Olympics threaten Utah’s long-term livability. Utah’s population is growing rapidly, and if dust and air-quality issues worsen, Arens says, “We’re going to have a harder time keeping people here who want to live in Utah, who want to work at Snowbird.”

“Failure,” says Fields, “is not an option.”

Employee awareness. The stakes resonate at the resort, which employs roughly 1,800 people in the winter. According to Fields, sustainability updates at the resort’s annual welcome-back meeting consistently draw the most attention. “Everybody puts their phones down,” he says. “Our employees want to know what we’re doing about an issue they’re very passionate about, and Great Salt Lake falls into that bucket. … If we’re talking about it at the dinner table, so are they.”

Across its educational partnerships, charitable investments, and coalition work, Snowbird has come to see advocating for Great Salt Lake as part of its responsibility in the region. “It’s much bigger than just snow for us,” says Fields.

Sun Valley: Stewardship Rooted in Community

If Snowbird’s work shows how climate impacts can ripple across a watershed, Sun Valley’s Bald Mountain Stewardship Project reflects a different facet of that widening scope. The pressures on Bald Mountain—tree mortality, parasite activity, and elevated wildfire risk—shape community safety and recreation in profound ways, which is perhaps one reason why the effort to remediate it extends beyond the ski area boundary, literally and figuratively.

Awareness and action in Sun Valley. Wildfires had burned the forests surrounding Bald Mountain in 2007 and 2013, leaving the resort an island of healthy trees ripe for infestations of dwarf mistletoe and the Douglas-fir beetle. The subsequent infestations, coupled with prolonged dry conditions, weakened large parts of the forest, creating a fuels cache that threatened the view, the recreation environment, and public safety.

In response, Sun Valley yarded hazard trees, applied lop and scatter treatments, and mastication treatments—moving the fuels, but not removing them. The resort knew a larger effort was needed to restore Bald Mountain, home to 2,533 skiable acres of terrain, a reality the wider community recognized as well—and local stakeholders wanted to do something about it.

That’s when, in 2019, the Bald Mountain Stewardship Project (BMSP) was initiated through the 5B Restoration Coalition, a collaborative convened by the National Forest Foundation (NFF) that includes Sun Valley Resort, the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, Blaine County, City of Ketchum, conservation groups, and local businesses.

Those voices helped shape the priorities. “Partners solidified the goals of the work into three important pillars: improving forest health, mitigating wildfire risk, and creating and maintaining recreational opportunities,” says Sun Valley public affairs and sustainability director Betsy Siszell.

The resulting landscape-scale, cross-boundary forest management plan encompasses roughly 3,331 acres within the resort’s special use permit area—and several thousand acres outside it.

Left: Sun Valley is part of a multi-agency healthy forest initiative that is managing and restoring forest depleted by pest infestations to reduce wildfire risk. Credit: Nick Lacey. Right: The program’s tree thinning activity has generated 4,000 cords of wood, distributed to Indigenous communities for home heating. Credit: Cooper Morton.

Left: Sun Valley is part of a multi-agency healthy forest initiative that is managing and restoring forest depleted by pest infestations to reduce wildfire risk. Credit: Nick Lacey. Right: The program’s tree thinning activity has generated 4,000 cords of wood, distributed to Indigenous communities for home heating. Credit: Cooper Morton.

Support and recognition. Thus far, as part of the ongoing work, roughly 427 acres have been thinned, and more than 47,100 trees have been planted. Nearly 4,000 cords of firewood from the restoration have been distributed to Indigenous communities for home heating through the “Wood for Life” program. Deliberate Whitebark Pine conservation efforts have earned Sun Valley a Whitebark Pine Friendly Ski Area certification, and the restoration coalition has embraced a unique funding structure rooted in community and collaboration.

Private donations from local nonprofits, foundations, and individuals helped fund early phases of the project and were then leveraged to secure additional federal dollars. Guests can also add a $5 donation to support forest health projects in the Sawtooth National Forest when purchasing lift tickets, passes, and rentals online; the first round of funding from that initiative will be allocated through NFF in 2026, says Siszell.

Community support has been integral in other ways, too. For example, volunteers and students have assisted with placing pheromone patches to protect species such as Whitebark Pine from insect infestation. “The local community has been instrumental,” Siszell says, “to ensuring our environment is well maintained, protected, and healthy.”

Sun Valley and the NFF also host annual field tours for residents, local business owners, elected officials, and media. Foresters, resort staff, contractors, and agency partners walk attendees through treatment areas and answer questions about the work underway. Siszell says this “real interaction with project sites” and has helped maintain interest and support as the project continues.

Most other visitors interact with the project by skiing and riding the nearly 380 acres of new gladed terrain that resulted from thinning treatments, and interpretive signage helps educate people about the restoration work, as does a video series on Sun Valley’s website. “This dynamic has created widespread support for the project in the Wood River Valley,” says Siszell.

The health of Bald Mountain has direct implications for public safety and the long-term viability of recreation in the area. And while the drivers are different from those at play with Great Salt Lake, the structure of the work is similar: a resort acting as one partner in a broader effort, backed by community engagement and sustained collaboration. “Community engagement and support will continue to be an essential element in the success of this work,” says Siszell.

Mt. Rose: The Slow Work of Systems Change

Mt. Rose-Ski Tahoe is organizing local diesel users to explore ways to make renewable diesel available and affordable.Sun Valley’s work is tangible, focused on healthier tree stands, reduced fuels, and renewed glades. But even projects not rooted in the landscape point back to a larger reality for ski areas: climate work increasingly requires coordination, persistence, and creative solutions. An effort at Mt. Rose–Ski Tahoe, Nev., for example, is centered not on ecosystems, but on the systems and markets that impact resort operations.

Mt. Rose-Ski Tahoe is organizing local diesel users to explore ways to make renewable diesel available and affordable.Sun Valley’s work is tangible, focused on healthier tree stands, reduced fuels, and renewed glades. But even projects not rooted in the landscape point back to a larger reality for ski areas: climate work increasingly requires coordination, persistence, and creative solutions. An effort at Mt. Rose–Ski Tahoe, Nev., for example, is centered not on ecosystems, but on the systems and markets that impact resort operations.

Driving change at Tahoe. Mt. Rose sustainability manager Anna Nason is working to transition the resort’s heavy machinery to renewable diesel, a drop-in fuel that can reduce lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions by up to 80 percent per gallon. The problem is cost. In Nevada, renewable diesel is at least a dollar more per gallon than petroleum diesel, a gap that makes it nearly impossible for the resort to adopt at scale.

Still, Nason has persisted. She has been meeting with local businesses, conservation groups, and operators to explore whether collective purchasing could make renewable diesel more viable. In the long term, she sees potential for public policy or incentive structures that could help shift the market.

Broader stakes. The broader stakes keep Nason motivated despite the challenges and slow pace of progress. “The potential for impact beyond our industry is what keeps me committed to this effort after some earlier conversations have ended in ‘not yet,’” she says.

Her work represents another facet of the industry’s climate response: addressing the structural barriers that stand between operators and lower-carbon operations. It’s unglamorous work, but it speaks to the same impulse that drives Snowbird’s educational programming and Sun Valley’s collaborative partnerships: the desire to create resilience that extends beyond the ski area boundary.

A Widening Scope

Ski areas are still doing critical, foundational work around decarbonizing, electrifying, and waste reduction. But these three stories show something about how industry climate efforts can also respond to the things communities need most: breathable air, healthy forests, and collaborative and persistent action.