One of the most confounding realities of the uphill transportation business is that successful operations depend largely on managing variables that are out of your control. That’s why an acute understanding of your ski area’s unique microclimate—and how the weather, especially wind, affects each of your aerial lifts—is key to informing decisions about safe lift operations. And while technology is there to assist, to spin a lift or not in windy conditions is ultimately a human decision—and a critical one to get right.

Ski area operators tend to be good about having processes and people in place to ensure the right decisions are made. After all, wind at ski areas is inevitable, but wind-related incidents are exceedingly rare.

There are various resources to help you know your weather (and other would-be resources that aren’t as helpful). Proper training, good communication, and a culture of trust also make a difference on windy days.

Wind is Weather

Get your weather forecasts from a reliable source that takes your specific location and elevation into account. Don’t use the weather app on your phone or that commercial weather site on your computer. “Most apps are fairly useless, especially when it comes to elevation,” says certified consulting meteorologist and owner of Nor’easter Weather Consulting Mallory Brooke.

“Be cautious of any national or global weather forecast outlets that are not geared specifically for mountain weather, as they often miss the local influences that mountain ranges and higher altitudes have on weather conditions,” advises OpenSnow meteorologist Alan Smith.

Accurate forecasts. Brooke, who has 30 ski area clients that she provides site-specific forecasts for, says that if you don’t contract with a consulting meteorologist, NOAA and the National Weather Service (NWS) is your next best option. She suggests developing a relationship with the forecasters at your local NWS office. At the very least, weather.gov allows you to point and click on the area map and the forecast accounts for elevation, “which is more than I can say for most other resources,” she says.

In addition, says Smith, NWS “local area forecast discussions” offer insights into local weather patterns and provide additional context.

Changes at NWS could have dramatic impacts on how accurately weather is forecast, though.

As of late July, more than 3,000 NWS positions were vacant, with over half of those vacancies the result of layoffs and early retirement offers from earlier this year. Unless key positions at NOAA and NWS are filled by winter, complicated winter forecasts may be more difficult to dial-in as fewer weather balloons go up and forecast products aren’t maintained due to lack of manpower.

Left to right: Rubble from blasting the upper terminal site for Sunday River’s eight-place chairlift, which lowered the grade of the terminal about 15 feet to help with wind resistance; The entire upper terminal site was regraded, which also helped ease access to adjacent trails.

Left to right: Rubble from blasting the upper terminal site for Sunday River’s eight-place chairlift, which lowered the grade of the terminal about 15 feet to help with wind resistance; The entire upper terminal site was regraded, which also helped ease access to adjacent trails.

Institutional knowledge. We must work with the recourses we have, though, which includes your acute understanding of your ski area’s microclimate. As Brooke says, “Microclimates are, essentially, why I have a job. Every mountain has its own.”

Air movement over and around a mountain results in unique conditions relative to the surrounding area. “Depending on what side of the mountain you’re on, you can have vastly different weather and have vastly different effects on operations, especially depending on your lift orientation and what kind of chair you have,” says Brooke.

OpenSnow’s forecasts do factor in terrain and elevation and are utilizing AI to help further refine forecasts in the future based on highly-localized terrain features, but both Smith and Brooke agree that those with their boots on the ground know their microclimate best.

“Ski area operators who are out in the field daily can often pick up on microscale factors that a weather model or forecaster might not always see from behind the computer screen, such as which areas tend to see more snow and wind than others,” says Smith.

In other words, it takes experience to understand the unique ways in which wind and weather affect each aerial lift at your mountain, and those with experience can look at a forecast from a reliable source and reasonably predict how the weather will affect operations on any given day.

This invaluable institutional knowledge should be broadly shared internally.

Under Pressure

Wind holds can ruin the day for guests and hurt the bottom line for ski areas, so operations teams do everything they can to keep lifts spinning safely. The decision to not run a lift most often requires evaluation and communication across multiple departments.

“It requires a high level of trust between lift ops and lift maintenance and ski patrol—we’re all on the same team and nobody’s out there pressuring anyone,” says Laurel Blessley, lift maintenance director at Big Sky Resort, Mont. “We all want to keep each other safe and the public safe, so having that trust is really, really important.”

No quit. The pressure to run lifts, especially on busy days, is real, says Aaron Kellett, general manager of Whiteface, N.Y., which stands more than 3,100 vertical feet above the valley and where strong winds are a part of life.

On slower days when the wind is forecast to be strong throughout, Kellett says they’ll make the call by, say, 1:30 p.m. to keep affected lifts closed for the rest of the day. “On a busy day, we might fight that out,” he says. If a lift can open by 3 p.m., they’ll do it.

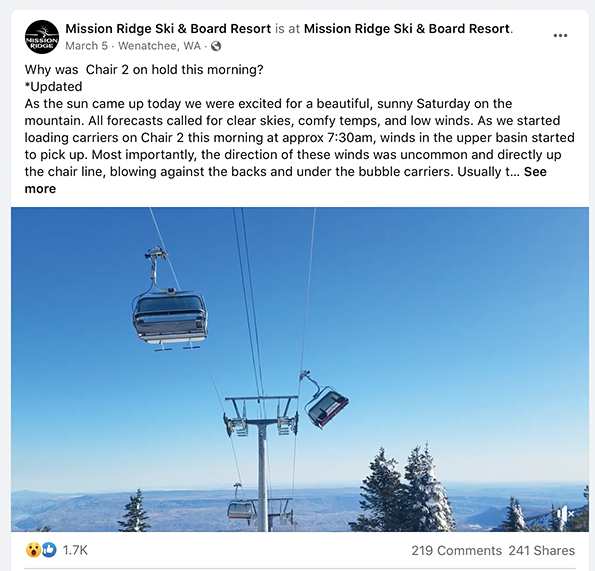

Mission Ridge’s March 2022 social post with a video of chairs swinging in the wind and an explanation of the situation provided by mountain ops was a model of transparency. However, “It doesn’t do anybody any good to push the limits on a busy day,” he says.

Mission Ridge’s March 2022 social post with a video of chairs swinging in the wind and an explanation of the situation provided by mountain ops was a model of transparency. However, “It doesn’t do anybody any good to push the limits on a busy day,” he says.

Sunday River, Maine, general manager Brian Heon says if the forecast is looking spicy, his team will decide which lifts to prioritize getting open in the morning based on wind direction and speed. As at Whiteface, they wait as long as possible to decide to shut lifts down for the day.

The value of being ready to open a lift, even with only an hour or two left in the day, is multifold: it shows guests the resort does everything it can to open lifts; lifts make end-of-day ingress or egress easier, especially for lodging guests; and it creates a positive decision-making culture that translates to guest communications, which builds trust both internally and externally.

Transparent communication. Guests aren’t always understanding when lifts are on wind hold. Mission Ridge, Wash., CMO Tony Hickok has found that “consistency in the communications approach is extremely important and helpful,” he says. “When you communicate enough info in a timely and regular manner, guests can trust in your message.”

Even when trust has been established, circumstances may require more than just a timely message. In March 2022, for example, an unusual upslope wind was hitting the quad bubble chair at Mission Ridge, causing major swing at the upper portion of the span, while conditions on the rest of the mountain “were really quite wonderful,” recalls Hickok. The resort’s mountain ops director suggested Hickok’s team use a video taken by a lift mechanic of the chairs swinging in the wind along with a more detailed written description of the situation on social media to provide context for guests as to why the lift was on hold.

The video and explanation was universally appreciated by guests and lauded by ski media, including us at SAM.

It was executed thanks to the interdepartmental trust and cohesion at Mission Ridge, the value of which, Hickok says, cannot be overstated. “Especially in the situations that are out of our control (like windy days), strong cultures can roll with that and work together to make the best of the situation,” he says.

What Shuts It Down

Determining whether it’s safe to spin a lift or not ultimately comes down to observing the effects of wind on the lift.

Key indicators. There are a few obvious things that signal unsafe conditions for lift operations. Among them: excessive lateral or longitudinal chair swing and notable haul rope movement; extreme comm line oscillation, especially in long spans with big bellies; detachable chairs swinging far enough to hit the trumpet when entering the top station; and when wind prevents bubble enclosures on bubble lifts from closing after leaving the upper terminal.

At Whiteface, says Kellett, lift operators at the top station are also trained to observe how winds affect guests unloading—a tail wind will push them off the chair faster and a headwind will keep them in the chair longer and make it difficult for them to push off, either of which can be unsafe.

Calling for backup. When any of these conditions occur, lift ops should call maintenance to come out for an evaluation. Even if a lift’s wind alarms haven’t gone off, “if you see something, say something, and we’ll come out,” says Big Sky’s Blessley. “I would rather come out and say, ‘everything’s fine,’ but take the time to see. So, my advice to operators is: when in doubt, call for help.”

As it is at many resorts, Whiteface and Sunday River ski patrollers get the same training as lift operators to learn how to determine unsafe lift conditions when it’s windy. Patrollers are often stationed near upper lift terminals and are the first ones on the hill in the morning, so they get first glimpse of how wind is affecting lifts. On breezy days, patrollers are asked to ride lifts often to provide real-time, in-the-air observations. “Patrollers riding lifts doing wind checks is super valuable because they know what to look for and can evaluate the situation from a user’s perspective,” says Heon.

Left to right: Sierra-at-Tahoe replacing the wind-damaged comm line on a lift that no longer has big trees to serve as a wind break after they were lost in a wildfire; A windy and snowy day at Jay Peak. Photo credit: Andrew Lanoue/Jay Peak, Vt.

Left to right: Sierra-at-Tahoe replacing the wind-damaged comm line on a lift that no longer has big trees to serve as a wind break after they were lost in a wildfire; A windy and snowy day at Jay Peak. Photo credit: Andrew Lanoue/Jay Peak, Vt.

Lift Design, Location, and Tech

When building a new lift or relocating an existing lift, wind resistance should be one of the top considerations in its design and location, according to lift manufacturers. A ski area’s experienced team is the best resource to make these determinations since, again, they know the mountain’s microclimate best. “The customers usually know the problem spots and have the best perspective on how to improve things there,” says Leitner-Poma of America’s (LPOA) Mike Manley.

Moderating wind impacts. Sometimes—for various reasons such as permitting, the need to connect one area to another, or lack of other viable options—a new lift’s alignment and location can’t be adjusted to account for wind. But there are a handful of things that can help with the impacts wind might have on the lift, according to Doppelmayr USA senior director of sales Geno Leslie. “A stand of trees or even an existing building can be used in the planning to reduce the effect of wind on the lift,” he says. “We have also seen carrier parking buildings used as wind blocks on certain installations, and even some areas relocate or replant trees in known wind paths to lessen impacts.”

Bigger lifts with heavier carriers and larger haul ropes—such as six-place detachables—perform better in wind than detachable quads or fixed-grips.

And, of course, the lower a lift’s profile, the better. “Once we have the alignment, our design philosophy is to keep the lift as low as possible,” says LPOA technical director Jeff Copeland.

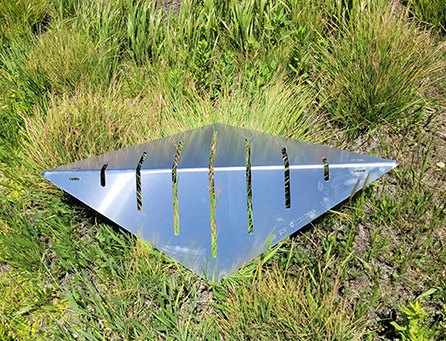

A dampening wing, several of which were installed on the lift’s comm line to reduce swing and oscillation in wind. Other, often costly, design and terrain modifications can be made, too. For example, Sunday River lowered the grade of the upper terminal site by roughly 15 feet when it removed an oft-wind-plagued detachable quad in favor of an eight-place chair, in part to make it more wind resistant. Whiteface installed a detachable quad in 2023 and, rather than going straight up the mountain, opted to include an angle mid-station to keep the profile on the side of a treeline that blocks the wind, and it’s been remarkably reliable as a result, says Kellett.

A dampening wing, several of which were installed on the lift’s comm line to reduce swing and oscillation in wind. Other, often costly, design and terrain modifications can be made, too. For example, Sunday River lowered the grade of the upper terminal site by roughly 15 feet when it removed an oft-wind-plagued detachable quad in favor of an eight-place chair, in part to make it more wind resistant. Whiteface installed a detachable quad in 2023 and, rather than going straight up the mountain, opted to include an angle mid-station to keep the profile on the side of a treeline that blocks the wind, and it’s been remarkably reliable as a result, says Kellett.

Major mods. Modifications can be made to existing lifts, too. After losing nearly all the surrounding trees to the Caldor Fire in 2021, Sierra-at-Tahoe’s (Calif.) West Bowl Express quad experienced frequent wind holds and had to replace the wind-damaged communication line during the 2022-23 season, when the resort was able to reopen after the fire. In response, Sierra worked with Doppelmayr to lower tower 15 (of 20) by 10 feet and install a trap sheave assembly on it, which increased the vertical load and tension on the adjacent towers, says mountain operations director Bryan Hickman. Sierra also installed dampening wings on the comm line—placed mid-span to reduce oscillation and swing in gusty conditions—and a wind fence.

“Since these modifications we’ve seen a measurable reduction in wind-related operational holds and comm line damage,” says Hickman. “The lift is now operating more reliably even under wind conditions that previously would have put the lift on a wind hold.”

Technology. Both LPOA and Doppelmayr include wind anemometers with new lifts. The gauges can be placed on any number of towers to monitor wind speed and direction, and, when wired to the lift’s control system, are configurable to automatically slow and/or stop a lift if wind speeds reach a preset threshold determined by the ski area. Manley says LPOA has recently been working with new technology for wind monitoring that’s less susceptible to damage from ice and other weather impacts. Doppelmayr’s Connect Control system tracks and records wind speeds and direction, allowing operators to look back and see trends, says Leslie.

All said, when the weather kicks up and decisions need to be made, your people are your greatest asset. “Listen to the teams running and maintaining the lifts,” advises Manley. “And do everything you can to keep those experienced staff members in the organization.”